By the end of a financial analysis, you should be able to answer two key questions: Will the company be solvent and able to repay its loans? Will it generate a higher rate of return than required by its financiers, thus creating value? Value creation and solvency are interconnected; a firm that creates value is generally solvent, while a company is likely insolvent because it hasn’t succeeded in creating value.

1. THE CONCEPT OF SOLVENCY

Here, we return to the concept used in “From earning to cash-flow”. A company is deemed solvent if it can settle all its obligations by liquidating its assets, meaning it could cease operations and sell off everything it owns. Since a company is not obligated to repay its shareholders, equity serves as a cushion during liquidation, absorbing any losses on assets and extraordinary costs.

Solvency is determined by two factors:

- The break-up value of the company’s assets

- The total amount of its debts

Asset values can vary significantly. For instance, a high-profile showroom may retain substantial value even outside the company’s operations, whereas specialized equipment in a heavy engineering plant might not. Additionally, secondary markets for assets differ; a car rental fleet may fetch a good price, while a foundry’s technical equipment might not. Typically, assets sell for less than their book value, leading to capital losses and potentially negative equity. This means lenders recover only a fraction of their claims, resulting in capital losses for them. Thus, a company’s solvency relies on its equity, adjusted from a liquidation perspective, relative to its debts and business risks. Losses erode equity and worsen solvency due to increased financial expenses and reduced tax benefits from debt. Often, companies respond by taking on more debt, which further amplifies financial costs and deepens losses.

When assessing solvency with the debt-to-equity ratio, it becomes clear that a company’s solvency can deteriorate swiftly during a crisis. For example, if a company’s debt equals its equity and both are at book value due to a stable return on capital, a downturn that reduces this return will significantly impact its solvency.

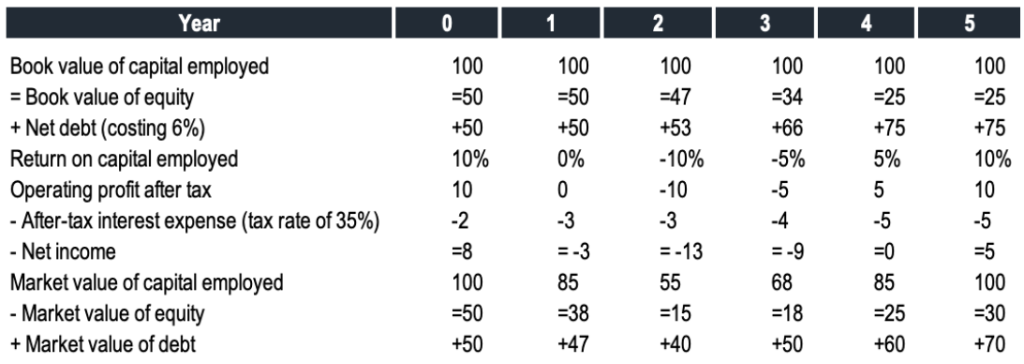

Here is a concrete example:

The company’s decline is evident. At its worst point, the market value of capital employed drops by 45% due to a shift from a positive to a negative return on capital employed. Similarly, the market value of debt falls from 100% to 75% of its nominal value, reflecting increased non-repayment risk as both return on capital employed and debt levels worsen. Meanwhile, the market value of shareholders’ equity plummets by 70%. Each year, the company must take on more debt to offset previous losses and maintain its capital employed. Initially at a ratio of 1, gearing skyrockets to 3 by year 5. In this scenario, equity dwindles, and lenders are unlikely to recover their full investment. This illustrates how debt can rapidly escalate during a crisis, potentially leading to restructuring or even bankruptcy due to mounting losses.

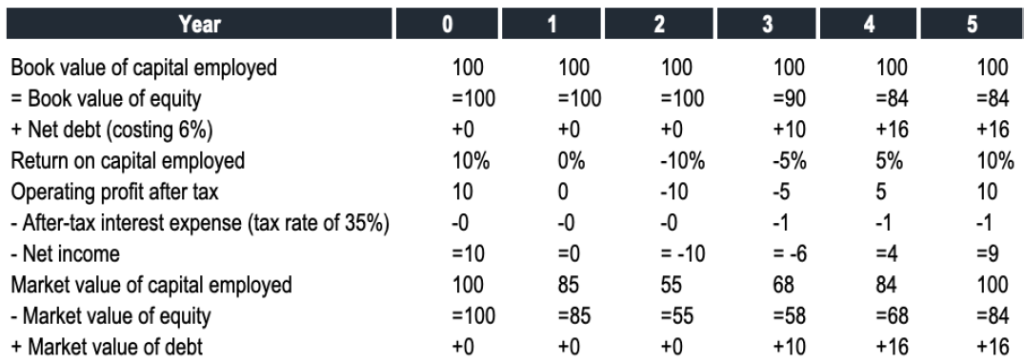

In contrast, had the company been debt-free when the crisis began, its financial performance would have been markedly different, as detailed in the following table:

By the end of year 4, the company returns to profitability, and its shareholders’ equity is only modestly impacted by the crisis. As a result, the first company, despite being economically similar to the second, faces severe financing challenges and is likely to fail as an independent entity. Historically, financial analysis focused on net assets – the difference between total assets and liabilities or assets net of debt. Net assets, a key measure of shareholders’ equity, were compared to total commitments.

Financial analysts often adjust net assets by subtracting goodwill or intangible assets, adding unrealized capital gains, and potentially valuing inventories at replacement cost. Calculating net assets becomes more complex with consolidated accounts due to minority interests and goodwill issues. Therefore, it is advisable to use individual accounts of the entities within the group and then consolidate net asset figures using the proportional method.

2. THE CONCEPT OF VALUE CREATION

A company can create value during a period if its after-tax return on capital employed surpasses the cost of the capital (both equity and net debt) used to finance that capital. To understand how to measure the required rate of return for shareholders and lenders, further details will be provided in upcoming sections. The concept of value creation and its measurement will be explored in depth in the following discussions.

3. FINANCIAL ANALYSIS WITHOUT THE NECESSARY ACCOUNTING RECORDS

When a company’s accounting documents are not available within the expected timeframe (typically less than three months after year-end), it often signals financial trouble. Analysts must then evaluate the extent of the company’s losses to determine if it can be salvaged or if it is destined for failure. In such cases, the focus shifts to estimating how much of the company’s debt can be recovered by lenders. Cash flow statements provide crucial insights into the link between net income and debt reduction. Interestingly, cash flow statements can sometimes be used in reverse to estimate earnings by examining the net decrease in debt. Given that financial information may be delayed or outdated, especially for troubled companies, the cash flow statement becomes an invaluable tool for assessing losses quickly.

Calculating net debt is straightforward as it involves assessing working capital components like receivables, payables, and inventories, as well as capital expenditures and asset disposals. Even with a subpar accounting system, a reverse cash flow statement can offer a rough estimate of earnings before official reports are available.

In some industries, cash flow might be a more reliable indicator of profitability than earnings. If cash declines without justifiable reasons—such as heavy capital expenditure, debt repayment, exceptional dividends, or significant business changes—this likely indicates operational losses, regardless of any adjustments to inventory or payment terms.