We’ve explored the basics of how corporate finance generally works:

- How does a company’s cash flow work?

- How does a company generate wealth?

- How does a company assess the value of its assets?

- How does the company analyze its margins?

- How does the company decide to take on debt, and how does it assess its return?

Let’s take a step back and analyze the behavior of the investor who would like to finance these companies. We will analyze the behavior of the investor who buys those instruments that the financial manager is trying to sell. An investor has the freedom to buy a security or not and, if they choose to buy, they can either hold it or resell it in the secondary market. The financial investor seeks two types of returns: the risk-free interest rate and a reward for taking on risk. We’ll delve later into these two types of returns in detail. But first, let’s make some general observations about capital markets.

1. CAPITAL MARKETS

The primary role of a financial system is to connect economic agents with surplus financial resources, such as households, with those in need of financial resources, like companies and governments. This relationship can occur either directly or indirectly. In the case of direct finance, those with excess resources directly fund those in need, with the financial system merely acting as a broker. This happens when an individual buys shares in a company or when a bank places a corporate bond issue with investors. On the other hand, in indirect finance, financial intermediaries like banks purchase securities issued by companies and then collect funds through deposits or issue their own securities to investors, thus performing intermediation. When you deposit money in a bank, the bank uses it to make loans to companies, and similarly, when you buy bonds from a financial institution, it finances other enterprises through loans. This intermediation is reflected in the intermediary’s balance sheet, which shows all resources and uses of funds, and its income statement, which reflects the difference between interest earned and paid, known as the spread.

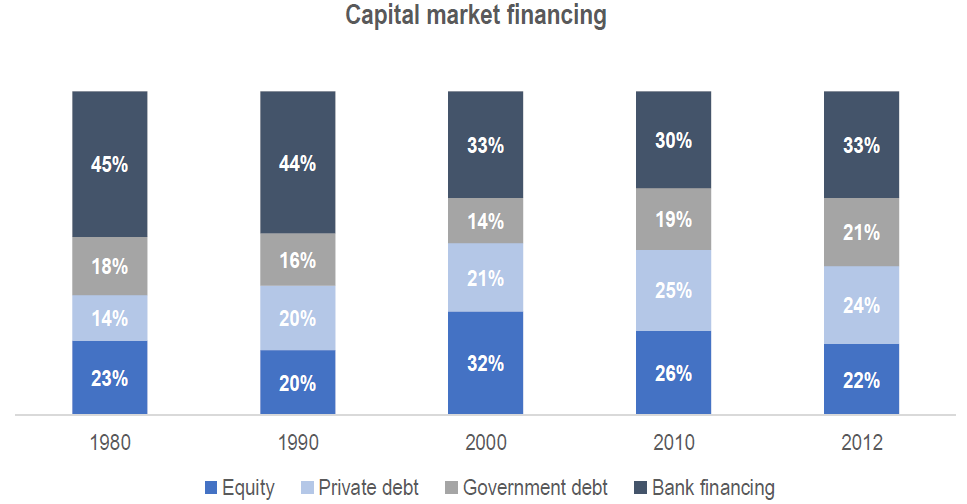

In today’s economy, disintermediation is becoming more prevalent, characterized by more companies and individuals engaging directly in capital markets, which is transforming the traditional operations of financial systems. In a bank-based economy, where the capital market is underdeveloped, debt financing predominates, with the central bank heavily influencing investment levels and overall economic growth through interest rates set for economic policy rather than market equilibrium. Inflation supports the credit-based economy by reducing the real cost of debt, making it attractive for companies to borrow heavily. However, this system is inherently flawed because it provides zero or negative real returns to investors, leading to low savings rates and a focus on tangible assets for protection against inflation. Conversely, in a market-based economy, companies meet their financing needs by issuing financial securities directly to investors, shifting the role of financial institutions towards placing companies’ securities with investors and aligning their rates with market trends. This shift has been driven by the rapid development of capital markets since the 1980s, due to positive real interest rates in bond markets and budget deficits financed through the bond market. Consequently, the financial manager now acts as a seller of financial securities, reflecting the shift towards capital market economies, where risks are tied to the value of securities rather than the receipt of cash flows, presenting different challenges compared to a credit-based economy. This evolving landscape underscores the dynamic nature of financial systems and the need for both investors and companies to adapt continuously to changing economic conditions.

2. THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM

The job of a financial system is to efficiently create financial liquidity for investment projects that promise the highest profitability and maximize collective utility. Unlike other markets, a financial system does more than balance supply and demand; it allows investors to convert current revenues into future consumption and provides current resources for borrowers at the cost of reduced future spending. What functions does a financial system perform? It offers various means of payment, such as cheques, debit and credit cards, and electronic transfers, facilitating the acquisition of goods and services without relying solely on bills and coins. Additionally, it pools funds to finance large, indivisible projects and subdivides company capital, allowing investors to diversify their investments. Without it, entrepreneurs would be limited to their own savings, hindering their ability to expand. The system also provides liquidity, enabling investors to hold assets in forms like shares and bank accounts, making it easier to retrieve their investments when needed.

Moreover, how does a financial system distribute resources? It spreads financial resources across time, space, and different economic sectors. It allows young couples to borrow for a house, people nearing retirement to save for future income needs, and developing nations to obtain resources for further development. Also, industrialized countries with excess savings can invest those surpluses in new economies through financial systems. By providing tools for risk management, such as mutual funds and insurance, the financial system allows individuals to reduce their exposure to risk through diversification. Insurance companies pool risks, making it feasible to insure against individual risks. Additionally, a financial system provides price information at a low cost, facilitating decentralized decision-making. Asset prices and interest rates serve as crucial information for individuals deciding how to consume, save, or allocate funds among different assets. Financial institutions conduct research and analysis on borrowers’ financial conditions, reducing costs for individual investors. Lastly, a financial system helps reduce conflicts between contracting parties by providing mechanisms for monitoring behavior and ensuring that parties uphold their contractual obligations. For instance, a fund manager must manage funds in the investor’s best interests; failing to do so can lead to a loss of confidence and replacement by a more conscientious manager.

3. BANKS & COMPANIES

Not so long ago, banks could be classified into commercial banks and investment banks. Commercial banks collected funds from individuals and lent to corporates, while investment banks provided advisory services, such as mergers and acquisitions and wealth management, and played the role of a broker in the placement of shares and bonds, without using their balance sheet. Over the last fifteen years, large financial conglomerates have emerged in both the USA and Europe, resulting from mega-mergers between commercial and investment banks, like BNP/Paribas, Citicorp/Travelers Group, Chase Manhattan/JP Morgan, and Merrill Lynch/Bank of America. This trend, facilitated by regulatory changes, reflects a shift towards the universal bank model, or “one-stop shopping,” driven by increasing internationalization and complexity. This model is particularly advantageous in business lines like corporate finance or fund management, where size provides a competitive edge.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, there has been a political push to split up large banking groups to separate deposits from market-related activities, aiming to confine speculative operations and prevent market activities from negatively impacting deposits. Today, large banking groups typically include several business lines. Retail banking caters to individuals and small- to medium-sized corporates, acting as intermediaries between those with surplus funds and those needing financing. With millions of clients, retail banks adopt an industrial organization, where a larger portfolio lowers risk due to the law of large numbers. Retail banking is highly competitive, with thin profit margins after accounting for risk. To add value, retail banks offer ancillary services such as various means of payment, cash flow management, and specific financial services like consumer credit, factoring, and leasing.

Corporate and investment banking (CIB) provides sophisticated services to large corporates, with a few thousand clients. These services include access to equity markets (Equity Capital Markets, ECM), where investment banks assist companies in preparing and executing initial public offerings and raising additional funds through capital increases. They also advise on the issuance of instruments that may become shares of stock, such as warrants and convertible bonds. In access to bond markets (Debt Capital Markets, DCM), investment banks help companies raise funds directly from investors through bond issuance. Additionally, CIB offers bank financing, including syndicated loans, bilateral lines, and structured financing, along with merger and acquisition (M&A) advisory services. These services, while not directly linked to corporate financing or capital markets, often accompany acquisitions. Access to foreign exchange, interest rate, and commodities markets for hedging risks is also provided, with banks using these desks for speculation as well.

Asset management banking serves institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals and some retail banking clients through mutual funds, sometimes utilizing products tailored by the investment banking division. Besides global banking groups operating across all banking activities, some players focus on targeted services like mergers and acquisitions and asset management (e.g., Lazard and Rothschild) or specific geographical areas (e.g., Mediobanca and Lloyds Bank). The 2008 crisis underscored the central role of banks in the economy as suppliers of liquidity and

indicators of investor risk aversion. Banks’ fundamental duty is to assess risk, repackage it, and eliminate diversifiable risk. Regardless of their business model, poorly managed banks were severely impacted, as seen with Northern Rock, Fortis, and Wachovia among retail banks, and Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers among investment banks, and Citi among universal banks. There is no single superior business model; some banks are simply better managed than others.

4. EFFICIENT MARKETS THEORY

An efficient market is one where prices of financial securities instantly reflect all relevant information. This means that current prices already incorporate the consequences of past events and all expectations about the future, making it impossible to predict price movements based on existing data. Essentially, only new information can cause price changes, leading to a random walk-in return.

Why does this happen? In a highly competitive market, investors adjust prices almost immediately as new information becomes available. To gauge market efficiency, we consider three tests: whether future prices can be predicted, how markets respond to events, and the impact of insider information. In a weak-form efficient market, past prices and trading volumes don’t help in predicting future returns, making technical analysis ineffective. Similarly, a semi-strong efficient market incorporates all publicly available information, causing prices to adjust immediately to news like earnings reports or company announcements, without any advance or prolonged impact. Regulators may halt trading before significant news to ensure fair dissemination of information.

In a strongly efficient market, insider information does not affect prices, provided that regulatory measures are effective. According to the efficient market hypothesis, professional investors, without insider knowledge, generally cannot outperform the market, as their performance may be slightly lower due to management fees.

Efficiency in a market depends on low transaction costs, high liquidity, and rational investor behavior. For instance, if a stock is expected to rise 10% tomorrow, its price will adjust today to reflect that anticipated gain. Efficient markets require accessible information, minimal transaction costs, and rational actions by investors. High liquidity ensures that well-traded securities adjust quickly to new information, while illiquid ones do so more slowly, leading to a risk premium for less efficient markets.

5. HOW THE INVESTORS BEHAVE

At any given time, investors fall into one of three categories: hedgers, speculators, or arbitrageurs.

Hedging

When an investor seeks to shield himself from risks he prefers not to take on, he is engaging in hedging. Essentially, hedging is a broad strategy applied to various investment decisions, such as aligning long-term investments with long-term financing or using equity rather than debt for risky ventures. For non-financial managers, hedging is a practical and sensible approach. It safeguards a company’s profit margins—the difference between revenues and expenses—from uncertainties related to technical, human, and market factors. By doing so, it helps manage the economic value of projects or business lines without being subject to the ups and downs of the capital markets.

For instance, a European company exporting to the U.S. might sell dollars forward in exchange for euros, securing a fixed exchange rate for its future dollar revenues. This action effectively hedges against fluctuations in currency exchange rates, ensuring stability in financial outcomes. In summary, when an investor hedges, they are opting to avoid taking on calculated risks, focusing instead on protecting their existing investments.

Speculation

Speculation involves taking on risk, unlike hedging, which aims to transfer it to others. So, what does it mean for an investor? A speculator bets on the future value of an asset—buying if they expect prices to rise and selling if they expect them to fall. For example, if an investor anticipates the dollar will strengthen, they might delay action, hoping for better conditions later. This is in contrast to hedging, where the goal is to avoid risk rather than accept it.

Traders, the professional speculators, buy and sell assets based on anticipated price movements, following the motto “Buy low, sell high.” But are all investors’ speculators? Indeed, every investor engages in some form of speculation when forecasting future cash flows. This speculation, grounded in analysis and skills, varies in its level of risk tolerance.

And why are speculators essential? They absorb risks that others avoid. For instance, a European company managing currency risk might buy dollars forward from a speculator, locking in an exchange rate for future payments. The speculator, in turn, takes on the risk of currency fluctuations. Similarly, when long-term financing needs exceed short-term savings, speculators step in to lend long-term, assuming the intermediation risk.

Speculative bubbles, where prices surge due to speculation rather than economic fundamentals, are exceptions rather than the rule. What defines a speculative market? It’s one where all participants are speculators. In such markets, if many believe an asset’s price will rise, their collective buying can drive up prices, encouraging others to buy. Conversely, if expectations shift, prices can plummet rapidly as speculators sell off their holdings to repay loans, deepening the decline.

Arbitrage

In contrast to speculators, who willingly take on risk, arbitrageurs aim to profit from small price discrepancies across different markets without assuming significant risk. For example, if Solvay shares are cheaper in London than in Brussels, an arbitrageur would buy them in London and sell them in Brussels. This action raises the price in London and lowers it in Brussels, helping the two markets reach equilibrium.

But how does this work without major risk? The arbitrageur profits from price differences without a net investment or exposure to market risk. While each transaction carries some risk, the overall strategy seeks to be risk-neutral. Nevertheless, practical arbitrage may involve risks, especially if transactions can’t be executed simultaneously or if liquidity is low. Arbitrage is essential for market efficiency. By correcting price discrepancies, arbitrageurs enhance liquidity and ensure that asset prices are consistent across markets. Their activity maintains market balance and prevents significant distortions.

It’s important to remember that investors often mix these roles. A speculator might also engage in arbitrage, and a hedger might use speculative strategies for part of their position. A well-functioning market needs a blend of hedgers, speculators, and arbitrageurs. A market composed of only one type of participant would struggle to stay balanced. Finally, the term “hedge funds” can be misleading. Despite their name, hedge funds often engage in speculative strategies rather than traditional hedging, as shown by their potential for significant gains or losses in short periods.