For economic progress, the time value of money must be universally applicable, even in a risk-free environment, giving rise to essential techniques like capitalization, discounting, and net present value. These aren’t just tools but vital reflexes that must be studied and mastered.

1. CAPITALIZATION

Consider a businessman who invests €100,000 in his business and sells it 10 years later for €1,800,000. Throughout this period, he receives no income from the business and invests no additional funds. Given this scenario, we need to determine the return on his investment. His profit is €1,700,000 (€1,800,000 – €100,000), resulting in a 1700% return over 10 years. Is this as impressive as it sounds? Initially, we might think to divide the 1700% return by 10 years to get an annual return of 170%. However, this approach is flawed. The value 170% has nothing to do with the annual return, which should compare the initial investment with the funds recovered after one year. Typically, calculating interest assumes a flow of revenue each year that can be reinvested, producing additional interest.

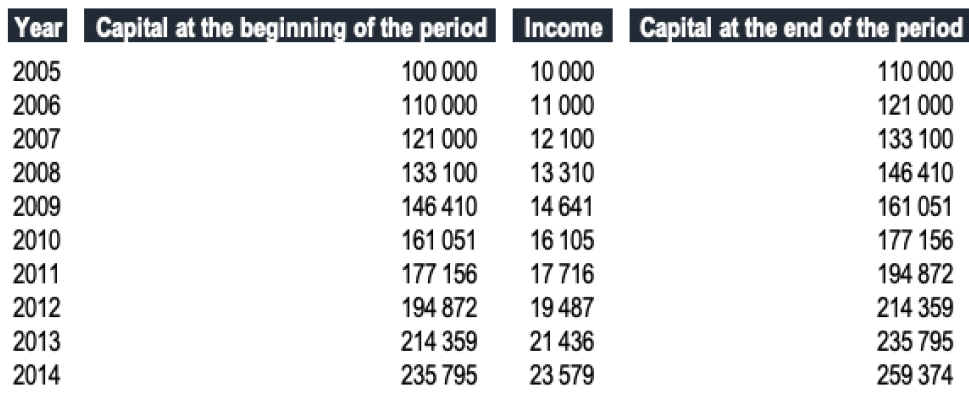

To find the accurate annual return, we must consider the compound interest effect, where reinvested income generates further earnings. Simply dividing the total return by the number of years neglects this compounding effect. Instead, we need to determine the annual rate that transforms €100,000 into €1,800,000 over 10 years with all income reinvested. Suppose we start with a hypothetical annual return rate of 10%. At the end of 2004, an investment of €100,000 at 10% will yield €10,000 in interest in 2005. This €10,000 is added to the initial investment, making the capital €110,000. In 2006, this amount earns 10%, producing €11,000, so the capital grows to €121,000, and so on.

Each year, the interest is reinvested, capitalizing the income. By 2014, this process of reinvestment and compounding interest leads to a final amount far greater than the initial investment. Through such an iterative process, we find that the investment grows from €100,000 to €259,374 demonstrating the significant impact of compound interest:

Thus, accurately calculating the annual return involves recognizing the effect of compounding, where each year’s interest earns additional interest. This method reveals a true annual return rate rather than the misleading simple division of total return by the number of years.

To easily calculate the future value of an investment, with an approximation of the interest at which you will invest your money, we need to use this capitalization formula:

\[V_n = V_o\times(1+r)^n\]where Vo is the initial value of the investment, r is the rate of return and n is the duration of the investment in years.

This equation helps us move from the initial capital to the terminal capital, with the terminal capital being a function of the rate (r) and the duration (n). Now, we can determine the annual return. In this example, the annual rate of return is not 170% but 33.5% (which is still quite impressive). Therefore, a 33.5% annual return transforms €100,000 into €1,800,000 over 10 years, assuming the income is reinvested annually at the same rate. To calculate the return on an investment without income distribution, we can use an analogy. This involves comparing it to an investment that over the same period turns the same initial capital into the same terminal capital, with annual income reinvested at the same rate. At 33.5%, an annual income of €33,500 for 10 years, plus the initial €100,000 investment repaid after the tenth year, equates to receiving €1,800,000 at the end of 10 years without any annual income distribution.

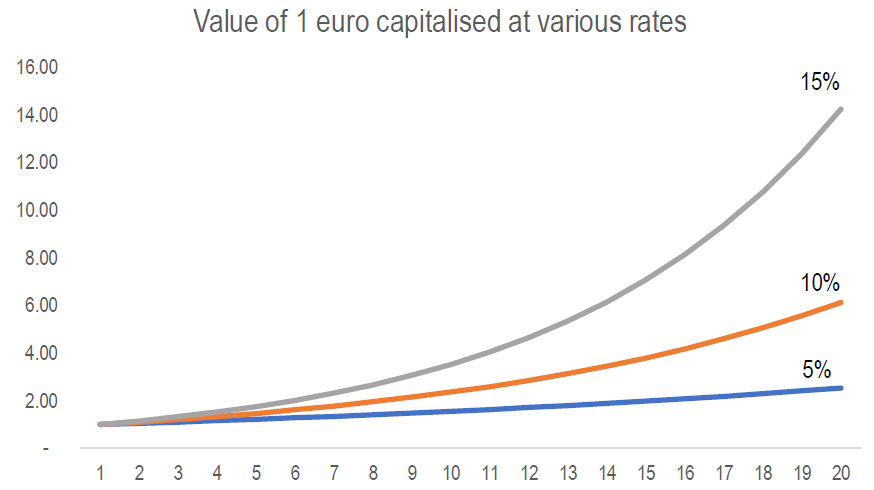

Over a long period, the effect of a change in the capitalization rate on the terminal value is significant:

This increase in terminal value is especially important in equity valuations. Take the earlier example of the businessman selling his company after 10 years. If he has received minimal income during this period, he will expect a higher amount when selling the business to ensure his investment was worthwhile. Without significant intermediate income, only a high terminal valuation can provide a return that makes economic sense. The same principle applies to industrial – investments. If an industrial project doesn’t generate income during its initial years, the eventual income must be substantial to yield a satisfactory return. The longer the delay in generating income, the greater the required income must be to compensate for the lack of returns in the earlier years.

Tripling one’s capital in 16 years, doubling it in 10 years, or simply seeking a 8,7% annual return all amount to the same thing, as the rate of return is consistent. Here, no distinction has been made between income, reimbursement, and actual cash flow. Whether income is paid out or reinvested, any change in the timing of income affects the rate of return.

To simplify, consider an investment of 100, which should be paid off at the end of year 1 with an accrued interest of 10. Suppose, however, that the borrower is negligent and the lender absent-minded, and the borrower repays the principal and interest one year later than planned. The return on a well-managed investment equivalent to the so-called 10% on our absent-minded investor’s loan can be expressed as:

\[V = V_o\times(1+r)^2\]Or

\[110 = 100\times(1+r)^2\]Hence r = 4.88%

This return is less than half of the initially expected return. What truly matters isn’t accounting or legal appearances but the actual cash flows. Any precise financial calculation must account for cash flow exactly at the moment it is received, not just when it is due. This principle ensures accurate assessment and decision-making based on real financial performance rather than merely anticipated timelines.

2. DISCOUNTING

What does that mean?

To discount means to calculate the present value of a future cash flow. Discounting today’s euros helps compare a sum that will not be produced until later. So, what is discounting? It involves “depreciating” the future by being more rigorous with future cash flows than present ones, as they cannot be spent or invested immediately. To do this, take tomorrow’s cash flow and apply a multiplier coefficient below 1, called a discounting factor. This factor expresses a future value as a present value, reflecting time’s depreciation.

Consider an offer to give you €1000 in five years. Applying a discounting factor of 0.6, the present value of this future sum is €600. Comparing it to other values, it’s preferable to receive €650 today rather than €1000 in five years, as the present value of €1000 five years out is €600, which is below €650. Discounting allows for comparing sums received or paid at different dates and is based on the time value of money, as “time is money.”

A sum received later is worth less than the same sum received today. Investors discount because they demand a certain rate of return. For example, if a security pays €110 in one year and you seek a 10% return, the most you would pay today (present value) is €100. This price ensures a 10% return on your investment of €100. If an 11% return is required, you would pay no more than €99.1 because the gain would be €10.9 (11% of €99.1), still resulting in a final payment of €110.

Discounting is calculated based on the investor’s required return. If the investment doesn’t meet or exceed expectations, the investor will seek better opportunities elsewhere. Discounting converts a future value into a present value, the opposite of capitalisation. While capitalisation converts present values into future ones, discounting does the reverse. For instance, €1,800,000 in 10 years, discounted at 33.5%, is worth €100,000 today. Conversely, €100,000 today will be worth €1,800,000 when capitalised at 33.5% over 10 years.

Discounting factors

To discount a sum, we use the same mathematical formulas as those for capitalising, but in reverse. Capitalising moves a sum forward in time, while discounting brings it back to the present. For example, to grow €100,000 today to €1,800,000 in 10 years, we use a capitalisation factor of 18, calculated as

\[(1+0.335)^10\]Conversely, to find the present value of €1,800,000 to be received in 10 years, we apply the discounting factor, which is the inverse of the capitalisation factor. Thus, we multiply €1,800,000 by 0.056, which is calculated as:

\[\frac{1}{(1+0.335)^{10}}\]This gives us €100,000, the present value of €1,800,000 in 10 years at a 33.5% rate.

More generally, the discounting formula is:

\[V_o = \frac{V_n}{(1+r)^n}\]Which is the exact opposite of the capitalisation formula. 1/(1+r)n is the discounting factor, which depreciates Vn and converts it into a present value Vo. It remains below 1 as discounting rate are always positive.

3. PRESENT VALUE & NET PRESENT VALUE

The present value (PV) of a security is calculated as the sum of its discounted cash flows:

\[PV = \sum_{n=1}^{N}\frac{F_n}{(1+r)^n}\]where Fn represents the cash flows, r is the discount rate, and n is the number of years. Securities also have a market value, which is the price at which they can be bought or sold on the secondary market. Net present value (NPV) is determined by subtracting the market value (Vo) from the present value:

\[NPV = \sum_{n=1}^{N}\frac{F_n}{(1+r)^n}-V_o\]If a security’s net present value (NPV) is higher than its market value, it’s undervalued and worth investing in for future gains. Conversely, if its NPV is lower than its market value, selling it is wise, as its value is expected to drop. Related to that, we’ll take a closer look at NPV in the next article, which deals with IRR, Internal Rate of Return.