Investors in financial securities encounter inherent risks due to the uncertainty surrounding future selling prices and interim cash flows. This article aims to clarify and quantify these risks, as well as explore their broader implications.

1. THE SOURCES OF RISK

Financial securities come with various risks, let’s first breakdown those:

- Industrial, commercial, and labour risks: these include a wide array of challenges, such as loss of competitiveness, new competitors, technological advancements, inadequate sales networks, and strikes. Such risks can reduce expected cash flows and, consequently, impact stock value.

- Liquidity risk: the danger of being unable to sell a security at its fair value, whether due to a liquidity discount or a lack of buyers.

- Solvency risk: the risk that a creditor may lose their entire investment if a debtor cannot fully repay, even if assets are liquidated, also known as counterparty risk.

- Foreign exchange (FX) risk: fluctuating exchange rates can reduce the value of assets or increase the debt burden when converted into the company’s reporting currency.

- Interest rate risk: securities holders are vulnerable to interest rate changes, which can result in capital losses or missed opportunities.

- Systemic risk: the potential collapse of the entire financial system due to disconnectedness and the domino effect of bankruptcies.

- Political risk: arising from political situations or decisions, such as nationalization, revolutions, or discriminatory tax policies that may restrict market access or capital repatriation.

- Regulatory risk: changes in laws or regulations that directly affect expected returns, particularly in sectors like pharmaceuticals, banking, and insurance.

- Inflation risk: the possibility that returns will fall below the inflation rate, leading to a loss in purchasing power, as seen in historical cases like Germany’s hyperinflation in the 1920s.

- Fraud risk: the risk of deceitful practices like insider trading.

- Natural disaster risks: these encompass events like storms, earthquakes, and other natural calamities that can destroy assets.

- Economic risk: associated with market cycles, business activity fluctuations, or shifts in labor productivity.

To summarize, risks can be categorized into two main types: economic risks, which impact cash flows directly and stem from the “real economy,” and financial risks, which arise from external financial events and do not directly affect cash flow but still influence the financial sphere. It’s crucial to recognize that risk is ever-present, and any serious investment analysis must start with a thorough risk assessment.

2. SECURITIES VALUES FLUCTUATION

All these risks can negatively impact a company’s financial performance and future cash flows. When a significant risk materializes and harms cash flows, investors often rush to sell their securities, driving down the security’s value. Additionally, if a company is perceived to be at high risk, some investors may avoid its securities altogether. Even before a risk becomes reality, uncertainty or volatility in anticipated cash flows can reduce a security’s value. Modern finance operates on the principle that investors aim to minimize the uncertainty of future cash flows. Since risk inherently increases this uncertainty, it is naturally reflected in the market value of a security. Investors focus on risk primarily in terms of how it impacts a security’s value—whether by altering cash flow expectations or influencing the discount rate applied to those cash flows.

In corporate finance, no fundamental distinction is made between the risk of an asset appreciating or depreciating; what matters is the existence of risk itself and its influence on investor behavior. Ultimately, all risks, regardless of their type, lead to fluctuations in the value of a financial security.

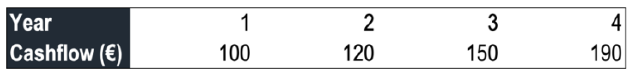

Let’s consider for example a security, with the following cash flows expected:

Imagine that the value of this security is estimated to be $2000 in 5 years. If we assume a 9% discounting rate, the value of the security today would be:

\[\frac{100}{1.09}+\frac{120}{1.09^2}+\frac{150}{1.09^3}+\frac{190}{1.09^4}+\frac{2000}{1.09^5}=$1,743\]And if a sharp in interest rates raises the discounting rate to 13%, the value will become:

\[\frac{100}{1.13}+\frac{120}{1.13^2}+\frac{150}{1.13^3}+\frac{190}{1.13^4}+\frac{2000}{1.13^5}=$1,488\]In this case, the value has fallen by 15% whereas cash flows have not changed. But if the company comes out with a new product and raise its cash flow by 20%, with the same discounting rate, the security’s value becomes:

\[\frac{120}{1.13}+\frac{144}{1.13^2}+\frac{180}{1.13^3}+\frac{228}{1.13^4}+\frac{2400}{1.13^5}=$1,786\]In this case the value increases for a reason that is specific to the company, not because of a fall in interest rates. Now, let’s assume that there is an improvement in the economic outlook and that the discounting rate falls to 10%. With same cashflows, the stock’s value would be:

\[\frac{120}{1.10}+\frac{144}{1.10^2}+\frac{180}{1.10^3}+\frac{228}{1.10^4}+\frac{2400}{1.10^5}=$2,009\]There are no changes in the stock’s characteristics and yet, the value has risen by 12%.

If price competition intensifies, cash flow projections might need to be adjusted downward by 10%, reducing the company’s value from €2 009 to €1,808—this decline is due to company-specific issues, not a market downturn.

For a European investor, this would mean a 10% loss, while a U.S. investor might see a 7% gain due to currency fluctuations. Securities with greater price volatility are considered riskier. In a market economy, risk is measured by price volatility—the more volatile, the riskier.

On the long-term, risk tends to decrease, with equities generally outperforming bonds, and bonds outperforming money-market investments.

3. MEASURING RETURN AND RISK

Expected return

To understand the relationship between a security’s return and its value, it’s important to see that they are essentially two sides of the same coin. The rate of return measures the total gain or loss on an investment, combining any income earned (like interest or dividends) and the change in the security’s value over a given period.

When looking at returns over a single period, the return is calculated by adding the income received during that time to any capital gain or loss from selling the security. However, because the future is uncertain, investors can’t predict their exact returns in advance, since both the final value of the security and the income generated may be unknown. To manage this uncertainty, investors rely on the concept of “expected return,” which is an estimate of the average return they might receive, based on different possible outcomes and their probabilities. For example, if a security has different chances of yielding a loss, a moderate gain, or a higher gain, the expected return is calculated as the weighted average of these possibilities, considering how likely each outcome is.

In simpler terms, the expected return gives investors an idea of what they might reasonably expect to earn, even though the exact result can’t be known in advance.

The variance

The relationship between risk and return is a fundamental concept in investing. Typically, the higher the risk associated with an investment, the more its returns can fluctuate, leading to greater uncertainty. For instance, a government bond is low-risk because its interest payments are almost guaranteed. In contrast, investing in an offshore oil drilling company involves much more uncertainty, where outcomes can range from complete loss to significant profit, depending on factors like oil prices and operational success.

Risk can be viewed as the degree of unpredictability in an investment’s returns, reflecting how much actual returns might differ from the expected average. This unpredictability is what makes an investment risky—the more variable the returns, the less certain the outcome.

To measure this risk, investors often rely on standard deviation. This metric indicates how much the returns of an investment are spread around the average expected return. A higher standard deviation suggests more variability in returns, indicating higher risk. While the expected return provides an estimate of potential earnings, standard deviation reveals the extent to which those returns may vary, offering a clearer understanding of the investment’s risk level.

Understanding both expected return and standard deviation allows investors to gauge not only what they might earn but also how much those earnings could fluctuate, helping them make more informed decisions.

4. WHAT ARE THE SPECIFIC RISKS?

In finance, risk is seen through the fluctuations in a security’s value, which lead to varying returns. Investors focus on how these fluctuations impact the overall value of their investment.

Value changes are driven by two main factors:

- Market-wide factors: These affect the entire market, like changes in interest rates or economic growth, causing most securities to move in the same direction, though to varying degrees.

- Company-specific factors: These impact only one company, such as a major new contract or new regulations.

These fluctuations correspond to two types of risk:

- Market risk: Linked to broader economic trends, affecting all securities and unavoidable through diversification.

- Specific risk: Unique to a single company, which can be mitigated through diversification.

5. BETA

Market risk is often measured by “beta” which indicates a security’s sensitivity to market movements. A beta above 1 suggests higher volatility than the market, while a beta below 1 suggests less. Specific risk represents volatility not tied to the market and is analyzed through the deviations in a security’s performance relative to market trends.

For security J, it’s mathematically obtained by performing a regression analysis of security returns versus market returns:

\[\beta_j=\frac{Cov(r_j,r_m)}{V(r_m)}\]

Here, the numerator is the covariance of the return of security J with that of the market, and the denominator is the variance of the market return. The beta is derived from the slope of the line that plots the security’s returns against the market’s returns, known as the characteristic line. For instance, Orange’s current beta is 0.86, meaning it’s less volatile than the overall market. This contrasts with its beta of 1.83 during the late 1990s, when the telecom sector was more dynamic and thus riskier.

Several factors can affect a company’s beta. For example, sectors that are highly sensitive to economic shifts, like automakers, generally have betas around 1. Companies with high fixed costs or significant debt tend to have higher betas due to increased volatility in their earnings. Additionally, a company’s beta can be influenced by the quality and transparency of the information it provides. Firms that offer less clear or less frequent updates about their performance often have higher betas, as investors factor in the uncertainty. Thus, beta reflects both the inherent risks of the sector and the specific financial and operational characteristics of the company.