In our analysis, we’ve focused on revenues and costs within a specific time frame. Now, let’s shift our

perspective to the end of the period, where we’ll analyze the remaining balances. This approach allows

us to assess net debt and accumulated wealth at a specific moment rather than over a period.

1. THE BALANCE SHEET: DEFINITIONS AND CONCEPTS

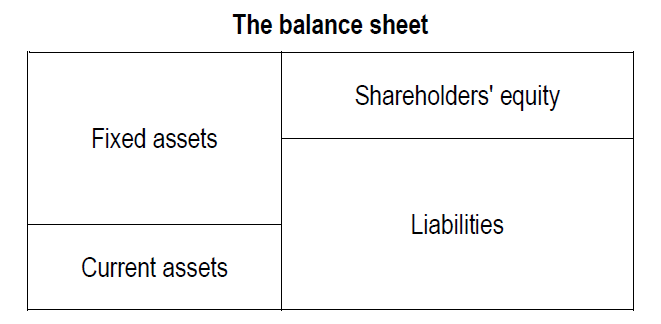

The purpose of a balance sheet is to list all the assets of a business and all of its financial resources at

a given point in time.

Main items

On the balance sheet, assets are categorized as follows:

- Fixed assets encompass all items necessary for the operating cycle that maintain value overtime, with depreciation, amortization, and impairment losses accounting for any decrease in value. These are further divided into tangible fixed assets (such as land, buildings, and machinery) and intangible fixed assets (like brands, patents, and goodwill), including long-term investments in other companies

- Inventories and trade receivables represent temporary assets formed during the operating cycle

- Marketable securities and cash, being company-owned, are also considered assets

Current assets, such as inventories, receivables, marketable securities, and cash, tend to circulate

throughout the operating cycle.

The balance sheet’s resource section includes:

- Shareholders’ equity, comprising capital from shareholders and retained earnings

- Liabilities consist of any borrowings, like bank loans or supplier credits, arranged by the business

In the framework of double-entry accounting, a company’s assets and resources must precisely

balance. This principle underpins the entire accounting system. When an item is acquired, it is either

capitalized as an asset or expensed. Capitalized items appear on the asset side of the balance sheet,

while expenses reduce earnings and subsequently shareholders’ equity. The corresponding double entry

involves either a decrease in cash (an asset) or an increase in a liability to the vendor. According

to accounting algebra, assets and resources (equity and liabilities) always have opposite signs,

ensuring the balance sheet remains in equilibrium.

Asset classification typically starts with fixed assets and ends with cash in European practice, while

North American and Japanese practice often begins with cash. Similarly, in the balance sheet’s equity

and liabilities section, Europeans typically begin with equity, whereas North Americans and Japanese

end with it.

In continental Europe, a “horizontal” format is common, with assets listed on the left and resources on

the right. In the United Kingdom, a “vertical” format is more prevalent, starting from fixed assets plus

current assets and deducting liabilities to arrive at equity. However, these are merely presentation

choices.

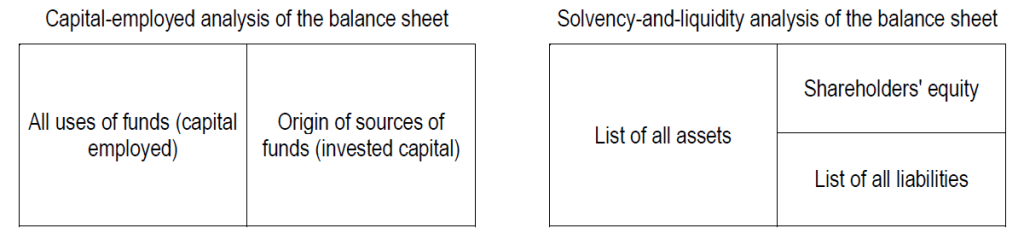

Two ways of analyzing the balance sheet

Two methods of balance sheet analysis exist: capital-employed perspective and solvency-and-liquidity

perspective.

In the capital-employed analysis, the balance sheet shows all the funds utilization for the company’s

operating cycle and traces the sources of funds. This analysis serves three primary objectives:

illustrating how a company finances its operating assets, computing the rate of return on either capital

employed or on equity, and initiating the valuation of the company’s equity as a going concern.

Conversely, in a solvency-and-liquidity analysis, a business is seen as a compilation of assets and

liabilities, with the disparity between them representing the book value of shareholder-provided equity.

This perspective involves listing all company assets and liabilities. The analysis serves three main

purposes: measuring the company’s solvency, assessing its liquidity, and providing an initial step in

valuing its equity in a bankruptcy scenario.

2. A CAPITAL-EMPLOYED ANALYSIS OF THE BALANCE SHEET

To understand the capital-employed analysis of the balance sheet well, we’ll focus on “stocks” instead

of inflows and outflows. Specifically, a capital-employed analysis divides the balance sheet into several

main sections.

Fixed assets

The fixed assets include all investments made by the business, as per our financial and accounting

definition. It’s helpful to distinguish between operating assets and non-operating assets unrelated to the

company’s main business activities, like land, buildings, and subsidiaries engaged in significantly

different industries. By isolating non-operating assets, we can assess the resources available to the

company during tough times, potentially through the sale of non-operating assets.

Working capital

The working capital represents the use of funds, including incurred but unsold operating costs

(inventories) and sales awaiting payment (trade receivables). It also covers charges incurred but not yet

paid (trade payables, social security, and tax payables), along with operating revenues from undelivered

products (advance payments on orders). The net balance of operating uses and sources of funds

constitutes working capital.

If the use of funds exceeds the sources of funds, working capital needs financing, which is more

common. Conversely, if the balance is negative, it signifies a source of funds generated by the

operating cycle, which is less frequent. Working capital is named as such because it reflects the cash

needed to cover financing shortfalls arising from day-to-day operations.

Sometimes, working capital is defined as current assets minus current liabilities, including marketable

securities, net cash, and short-term financial and banking borrowings. However, we see this definition

as improper since it mixes items from both the operating and financing cycles. Expressions like “working

capital needs” or “requirements in working capital” are synonyms for working capital. It can also be

divided into operating working capital and non-operating working capital.

Operating working capital comprises the following accounting entries:

| Inventories | Raw materials, goods for resale, products and work in progress, finished products |

| + Trade receivables | Amounts owed by customers, prepayments to suppliers and other trade receivables |

| – Trade payables | Amounts owed to trades suppliers, social security and tax payables, prepayments by customers and other trade payables |

| = Operating working capital |

Only the regular number of operating sources of funds is factored into the calculation of operating

working capital. Unusually extended payment terms granted by suppliers should not be considered part

of normal operating working capital. If such extended terms are permanent, the abnormal portion should

be treated as a source of cash, effectively making the suppliers act as the company’s bankers.

Inventories of raw materials and goods for resale should only be valued at their standard amount.

Exceptionally large inventory figures should never be included in the calculation of operating working

capital. If necessary, the excess portion of inventories or inventory held for speculative purposes can be

treated as a high-risk short-term investment.

Working capital is entirely separate from the methods used to evaluate fixed assets, depreciation,

amortization, and impairment losses on fixed assets. However, it is influenced by inventory valuation

methods, deferred income and costs (spread over one or more years), and the company’s provisioning

policy for current assets and operating liabilities and costs. While we’ve considered the timing

discrepancies between inflows and outflows during the operating cycle, we’ve always assumed that

capital expenditures are paid for upon purchase and that non-recurring costs are paid for when they are

recognized in the income statement. However, there may be timing differences, leading to what is

termed non-operating working capital.

Non-operating working capital, while not robust from a theoretical standpoint, is challenging to predict

and analyze because it depends on individual transactions, unlike operating working capital, which is

recurring.

Capital employed

Capital employed includes a company’s fixed assets and its working capital (both operating and nonoperating). It represents the net amounts allocated by a business to its operating and investing cycles

and is also referred to as operating assets. This capital is financed primarily by shareholders’ equity and

net debt, often consolidated as invested capital.

Shareholders’ equity

Shareholders’ equity consists of the initial capital contributed by shareholders during the company’s

formation and subsequent capital injections, along with earnings retained by the company and allocated

to reserves.

Net debt

The company’s gross debt encompasses all forms of debt financing, regardless of maturity, including

medium and long-term borrowings (due in more than one year) and short-term bank or financial

borrowings (due in less than one year). Net debt, on the other hand, deducts cash, equivalents (such as

petty cash and bank accounts), and marketable securities from gross debt. These deductions represent

assets that could potentially offset or entirely eliminate the gross debt, as they involve the company

lending money to banks or financial markets.

3. A SOLVENCY AND LIQUIDITY ANALYSIS OF THE BALANCE SHEET

The examination of the balance sheet from a solvency-and-liquidity viewpoint provides an overview of

the company’s assets and liabilities at the close of the fiscal year. This analysis serves various

purposes:

- Shareholders utilize it to enumerate the company’s assets and liabilities, acknowledging the potential need for revaluation of these figures

- Creditors employ it to evaluate the risk associated with extending loans to the company

In capitalist systems, shareholders’ equity serves as the ultimate guarantee in case of liquidation,

prioritizing creditor claims over those of shareholders.

Balance sheet liquidity

Prior to conducting a liquidity analysis, a systematic classification of balance sheet items is imperative.

Liabilities are arranged based on their repayment timeline, distinguishing between short-term obligations

(due in less than one year), medium to long-term liabilities (due in more than one year), and those not

yet due for repayment. Similarly, assets can be categorized by duration as follows:

- Current assets, typically expected to vanish from the balance sheet within the next year

- Fixed assets, anticipated to persist on the balance sheet beyond the upcoming year

In a liquidity assessment, liabilities are categorized by their maturity date, investments by their duration,

and assets as follows:

- Assets are considered liquid if they can be converted into cash within the normal operating cycle, typically within a year. This primarily includes inventories and trade receivables, barring unusually prolonged operating cycles

- Assets not intended for sale in the regular course of business, regardless of their type (e.g., head office, plant), are deemed fixed (non-current) and illiquid

The liquidity of a balance sheet stems from the swifter monetization of assets compared to the

repayment of liabilities. While the maturity schedule of liabilities is predetermined, the liquidity of current

assets remains uncertain due to potential sales setbacks or inventory devaluations. This contrast

between the structured maturity of liabilities and the uncertain liquidity of assets is a critical aspect.

Consequently, short-term creditors assess the gap between a company’s asset liquidity and its liability

structure, often requiring a buffer of current assets exceeding short-term liabilities to ensure safety.

Hence, the fundamental financial principle dictates that a company must maintain current assets due for

monetization within one year at least equivalent to its liabilities maturing within the same period.

Solvency

From an accounting perspective, a company may be deemed insolvent when its shareholders’ equity

becomes negative, indicating that its liabilities surpass its assets. Occasionally, solvency is interpreted

more broadly, denoting the company’s capability to settle its debts as they come due.

Net asset value

This concept focuses on solvency and aims to determine shareholders’ investments by assessing the

company’s value as the difference between its assets and liabilities. Net asset value is primarily an

accounting and, in some cases, tax-related term rather than a financial one. The book value of

shareholders’ equity is calculated as everything owned by the company minus its existing or potential

liabilities. Financial experts often refer to net asset value, which can be confusing for non-specialists,

who might interpret it as total assets minus depreciation, amortization, and impairment losses. Book

value of equity is thus equal to the sum of fixed assets and current assets minus all liabilities of any

kind.

When a company is sold, the purchaser tends to take an even more rigorous approach, which involves:

- considering contingent liabilities that aren’t listed on the balance sheet

- excluding assets that have no value, such as many intangible assets due to their accounting complexity

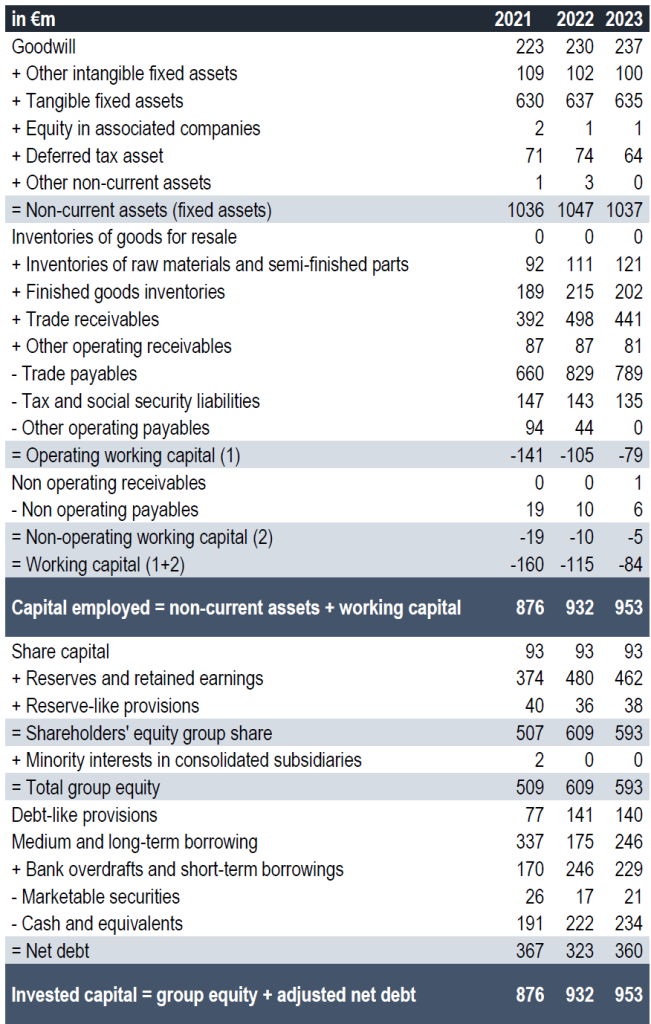

4. EXAMPLE OF A CAPITAL-EMPLOYED BALANCE SHEET

To highlight the different concepts of this article, here is an example of a capital-employed balance

sheet: