The earlier articles detailed the cash flow statement’s structure, which compiles all receipts and payments within a specific period and determines the change in net debt position, as well as the income statement’s structure, which summarizes all revenues and expenses over a period. At first glance, these two seemingly distinct methods might appear unrelated. However, common sense suggests that a wealthy woman will eventually have money in her pocket, while a poor woman is likely to struggle financially—unless she happens to acquire wealth along the way. Despite the complex dynamics of a business causing discrepancies between profits and cash, they eventually align. This article aims to bridge the gap between the cash flow and earnings methods.

1. ANALYSIS OF EARNINGS FROM A CASH FLOW PERSPECTIVE

This section is included merely for explanatory and conceptual purposes. Even so, it is vital to understand the basic financial workings of a company.

Operating Revenue

Operating receipts should align with sales for the same period, but they differ because:

- Customers might be allowed a payment period

- Payments for invoices from the previous period may be received in the current period

Therefore, operating receipts match sales only if sales are paid immediately in cash. Otherwise, they result in a change in trade receivables.

Sales for the period – Increase in trade receivables (or + reduction in trade receivables) = Operating receipts

Changes in inventories and work in progress

As previously discussed, in by-nature income statements, the difference between production and sales is accounted for by changes in inventories of finished goods and work in progress. However, this is simply an accounting adjustment to exclude from operating costs those expenses that do not concern sold products. It does not affect cash flow. Therefore, changes in inventories must be reversed in a cash flow analysis.

Operating costs

Operating costs differ from operating payments similarly to how operating revenues differ from operating receipts. Operating payments align with operating costs for a specific period only when adjusted for:

- Timing differences due to the company’s payment terms (such as credit granted by its suppliers, etc.)

- The fact that some purchases are not used within the same period. The difference between purchases made and purchases used is adjusted for through changes in inventories of raw materials

These timing differences result in:

- Changes in trade payables in the first instance

- Differences between raw materials used and purchases made, which equate to changes in inventories of raw materials and goods for resale

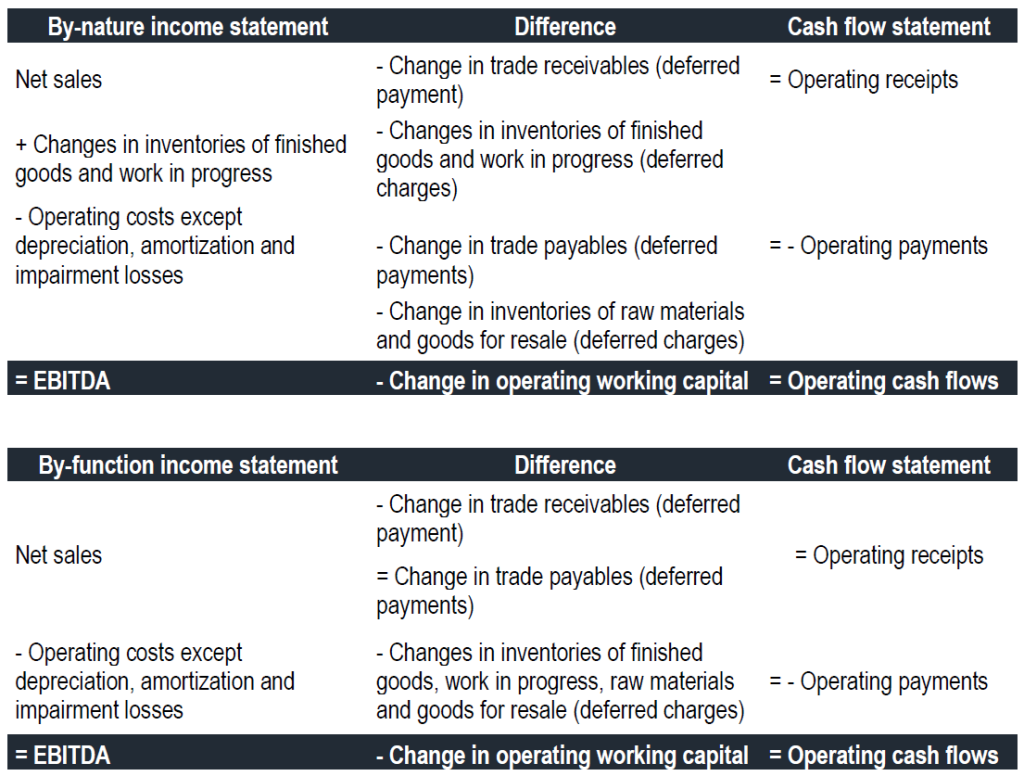

The total of the timing differences between operating revenues and costs, as well as between operating receipts and payments, can be summarized as follows for both by-nature and by-function income statements:

During a specified timeframe, the shift in operational working capital indicates either a necessity for funding that needs to be included in or deducted from other funding requirements or resources.

If positive, it indicates a need for financing, and we denote it as an expansion in operational working capital. If negative, it signifies a fund surplus, and we denote it as a contraction in operational working

capital. The alteration in working capital simply reflects a straightforward temporal variance between the balance of operating cash flows (operating cash flow) and the value generated by the operating cycle (EBITDA). It’s crucial to bear in mind that timing disparities may not always be minor, of restricted significance, brief, or negligible in any way.

Capital expenditure

Capital expenditures lead to a change in what the company owns without an immediate increase or decrease in its overall wealth. Consequently, they are not directly reflected on the income statement. However, capital expenditures do have a direct impact on the cash flow statement. From the perspective of capital expenditure, a fundamental disparity separates the income statement and the cash flow statement. The income statement spreads the cost of capital expenditure over the entire lifespan of the asset (via depreciation), whereas the cash flow statement records it solely in the period of acquisition. A company’s capital expenditure process results in both cash outflows that do not decrease its wealth and the accounting recognition of impairment in the acquired assets through depreciation and amortization, which does not entail any cash outflows. Therefore, there isn’t a direct correlation between cash flow and net income for the capital expenditure process.

Financing

Financing revolves around the cycle of inflows and outflows. Sources of financing (such as new borrowings, capital increases, etc.) are not depicted on the income statement, which only displays the compensation paid on certain resources, like interest on borrowings but excludes dividends on equity. Outflows that represent a return on sources of financing can be interpreted either as costs (such as interest) or as a distribution of wealth generated by the company among its equity capital providers (i.e., dividends). While the differentiation between capital and interest payments is not crucial in the cash flow statement, it holds significance in the income statement.

To simplify matters, assuming no timing disparities between the recognition of a cost and the corresponding cash outflow, it’s necessary to distinguish between:

- Interest payments on debt financing (financial expenses) and income tax, which influence the company’s cash position and its earnings

- The compensation disbursed to equity capital providers (dividends), impacting the company’s cash position and earnings allocated to reserves

- Initiating new borrowings, repaying borrowings, capital increases, and share buybacks, affecting its cash position but having no bearing on earnings

Lastly, corporate income tax stands as an expense on the income statement and a cash payment to the State, providing the company with various essential services and entitlements, such as police, education, roads, etc.

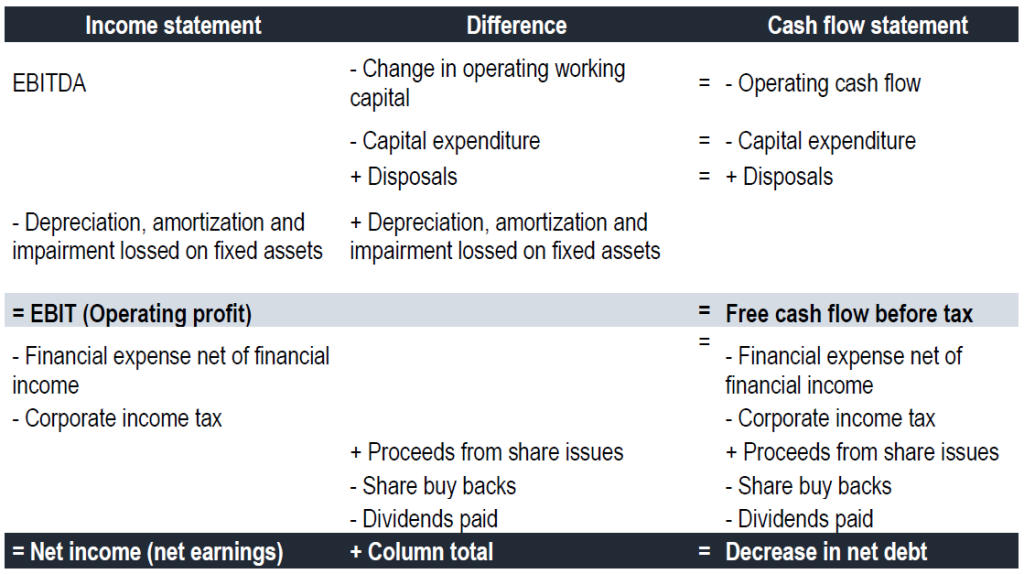

Now, we can complete our table and proceed from earnings to a reduction in net debt.

2. THE CASH FLOW STATEMENT

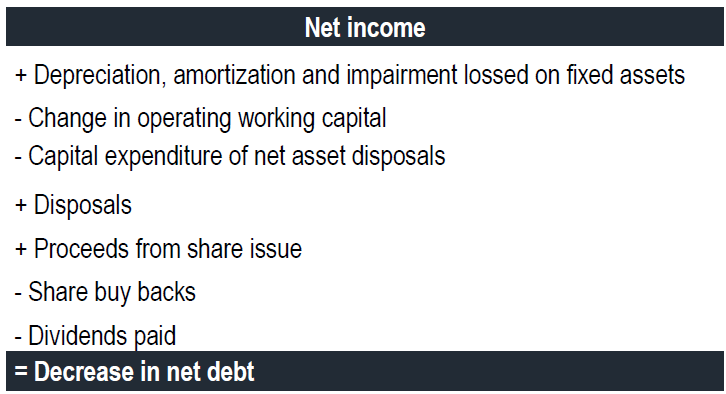

Using the same table, we can reverse our approach to account for the decrease in net debt based on the income statement. To achieve this, we only need to reverse the movements depicted in the central column and add them back to net profit.

The following rationale aids our effort to categorize the different line items facilitating the transition from net income to a decrease in net debt. Net income typically contributes to “cash on hand.” However, we also need to reintroduce certain non-cash expenses (depreciation, amortization, and impairment losses on fixed assets) that were subtracted on the way down the income statement but do not affect cash, to calculate what is termed cash flow. Cash flow is incorporated into “cash on hand” only after accounting for timing discrepancies related to the operating cycle, as measured by changes in operating working capital. Finally, the investing and financing cycles generate uses and sources of funds that do not immediately impact net income.

From net income to cash flow

As just discussed, depreciation, amortization, impairment losses on fixed assets, and provisions are non-cash expenses that do not affect a company’s cash position. From a cash flow perspective, they are treated similarly to net income. Therefore, they are added back to net income to demonstrate the total internally generated financing by the company. These components together form the company’s cash flow, which accountants allocate between net income on one side and depreciation, amortization, and impairment losses on the other, in accordance with relevant accounting and tax regulations. Cash flow can thus be calculated by adding certain non-cash charges net of write-backs to net income.

The simplicity of the cash flow statement may have been apparent, but it might raise eyebrows among traditional accountants. They might struggle to accept that financial expenses should be treated similarly to repayments of borrowings. Using debt to cover financial expenses differs from replacing one debt with another: the former depletes the company’s resources, whereas the latter constitutes liability management. Consequently, traditionalists have introduced the concept of cash flow.

We must emphasize that we recommend computing cash flow before considering any capital gains (or losses) on asset disposals and before accounting for non-recurring items, simply because they are one-time occurrences. Cash flow is only relevant in a cash flow statement if it is not artificially inflated by the inclusion of non-recurring items.

Cash flow is not as straightforward a concept as EBITDA. Nonetheless, a direct correlation can be established between these two concepts by deriving cash flow from the income statement using the top-down method.

EBITDA

– Financial expense net of financial income

– Corporate income tax

= Cash flow

Or this :

Net income

+ Depreciation, amortization and impairment losses

+ Capital losses/gains on asset disposal

+ Other non-cash items

= Cash flow

Cash flow is subject to the same accounting policies as EBITDA and remains unaffected by the accounting treatments applied to tangible and intangible fixed assets. It’s worth noting that the calculation method slightly differs for consolidated accounts. In consolidated accounts, the contribution to consolidated net profit from equity-accounted income is replaced by the dividend payment received. This adjustment arises because the parent company does not directly receive the earnings of an associate company, as it lacks control over it, but instead receives dividends.

Moreover, cash flow is computed at the group level without considering minority interests. This approach seems logical since the parent company controls and manages the cash flows of its fully consolidated subsidiaries, even if it does not own them entirely. In the cash flow statement, minority interests in controlled subsidiaries are only reflected through the dividends they receive.

Lastly, it’s important to be cautious regarding cash flow, as there are various definitions of it across different companies. While the preceding definition is commonly used, some professionals may simply refer to free cash flows, cash flow from operating activities, and operating cash flow as “cash flow.” Therefore, it’s advisable to confirm which specific cash flow they are referring to.

From cash flow to cash flow from operating activities

To transition from cash flow to cash flow from operating activities, we must adjust for timing disparities in cash flows associated with the operating cycle. This yields the following formula:

Cash flow from operating activities = Cash flow − Change in operating working capital.

Note that the term “operating activities” is used here in a broad sense, encompassing financial expenses and corporate income tax.

Other cash movements

Having isolated cash movements stemming from the operating cycle, we can now allocate the remaining movements to the investment and financing cycles. The investment cycle comprises:

- Capital expenditures (acquisitions of tangible and intangible assets)

- Disposals of fixed assets, indicating the selling price of fixed assets without consideration of capital gains or losses

- Changes in long-term investments (e.g., financial assets). Where applicable, we may also consider the impact of timing disparities in cash flows generated by this cycle, particularly non-operating working capital (e.g., amounts owed to suppliers of fixed assets)

The financing cycle comprises:

- Cash inflows from capital increases, dividend payments (i.e., payments from the previous year’s net profit), and share buybacks

- Changes in net debt resulting from repayments of (short-, medium-, and long-term) borrowings, new borrowings, changes in marketable securities (short-term investments), and changes in cash and equivalents

This process brings us back to the cash flow statement, employing the indirect method, which begin with net income and categorizes cash flows by cycle (i.e., operating, investing, or financing activities).

In practice, most companies present a cash flow statement starting with net income and progressing to changes in “cash and equivalents” or “change in cash,” although this latter concept is poorly defined, with some companies including marketable securities while others deduct bank overdrafts and short-term borrowings.

Net debt more accurately reflects a company’s level of indebtedness compared to cash and cash equivalents or cash and cash equivalents minus short-term borrowings, as the latter represent only a fraction of a company’s debt position. While changes in net debt can provide meaningful insights, changes in cash and cash equivalents are often less relevant, as it is relatively simple to inflate cash on the balance sheet at the reporting date by acquiring long-term debt and depositing the proceeds in a bank account. While cash on the balance sheet increases, net debt remains unchanged.