After examining company cash flows, it’s imperative to delve into how a company generates wealth. In this section, we’ll explore the income statement to elucidate how a company’s different cycles contribute to wealth creation.

1. WEALTH MANAGEMENT

What would your answer be to the following questions?

- Does purchasing a house make you richer or poorer?

- Would your answer change if you used a loan to buy it?

There can be no doubt as to the correct answer. The answer is straightforward. Whether you buy the house outright or with a loan, your overall wealth remains the same as long as you pay the market price. Many people confuse cash with wealth, but they’re different concepts. It’s important to analyze transactions for both cash flow and wealth effects. For instance, buying an apartment doesn’t change your wealth but reduces your cash. Taking a loan doesn’t affect your wealth but increases your cash.

Though taking on debt adds to financial resources and obligations, it doesn’t change net worth. When buying property with cash, your assets change (cash decreases, real estate assets increase), but your net worth stays the same. Spending money doesn’t always reduce wealth, just as receiving funds doesn’t necessarily increase it. The income statement lists everything that boosts or decreases a company’s wealth, including all the gains (revenues) and losses (expenses or costs). Every business aims to grow wealth, which involves both. Essentially, earnings show the gap between what adds to wealth and what takes away from it.

| + Revenues | + Gross additions to wealth |

| – Costs | – Gross deductions from wealth |

| = Earnings | = Net additions to wealth (deductions from) |

Earnings are positive when wealth increases and negative when it decreases. While the income statement and cash flow statement serve different purposes, not all cash flows impact earnings. Similarly, some revenues and costs don’t affect the company’s cash position and thus aren’t included in the cash flow statement.

Earnings and the Operating Cycle

The operating cycle is essential for a company’s wealth. It includes both the addition to wealth, like selling products and services recognized in the market, and deductions from wealth, such as raw material consumption, labor, and external services. Ultimately, a business aims to boost wealth through its operating cycle.

| Additions to wealth | + Operating revenues |

| Deductions from wealth | – Cash operating costs |

| = Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) |

In simpler terms, the outcome of the operating cycle is the difference between operating revenues and the cash spent on operating costs to generate these revenues. We call it gross operating profit or EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). It’s referred to as ‘gross’ because it focuses solely on the operating cycle, calculated before non-cash expenses like depreciation and amortization, as well as before interest and taxes.

Earnings and the Investment Cycle

Investment activities are not directly listed on the income statement. From a wealth perspective, investments represent the use of funds that retain some value. When you invest, you’re using liquid funds to purchase an asset without destroying wealth. Therefore, investments don’t directly appear on the income statement.

However, the value of investments can change over a financial period:

- It may decrease due to wear and tear or obsolescence

- It may increase if the market value of certain assets rises. Typically, increases in value are only recorded if the asset is sold, following the principle of prudence

The decrease in the value of a fixed asset, resulting from its use by the company, is reflected in depreciation and amortization. Impairment losses or write-downs on fixed assets acknowledge the loss in value unrelated to day-to-day use, such as the unforeseen decline in the value of intangible assets (like goodwill or patents), tangible assets (such as property or equipment), or investments in subsidiaries. Depreciation and amortization on fixed assets are considered ‘non-cash’ expenses, as they reflect accounting assessments of value loss. These are included in operating costs and provisions.

The distinction between operating costs and fixed assets

While defining investment from a cash flow perspective, we acknowledge that our approach contrasts with the traditional presentation, particularly for those familiar with accounting:

- Anything consumed during the operating cycle to create something new is part of that cycle. Creation inherently involves some form of destruction

- Anything used without direct destruction, retaining its value, belongs to the investment cycle. This constitutes an immutable asset, or in accounting terms, a fixed asset (termed ‘non-current asset’ in IFRS)

For example, in making bread, a baker uses flour, salt, and water, all contributing to the final product. Labor, though essential in transforming raw materials, retains value only in the process. Additionally, the baker requires a bread oven, vital for production but not consumed. While subject to wear and tear, the oven endures through repeated use. This distinction between operating costs and fixed assets may seem straightforward, yet proves as nuanced as distinguishing between investment and operating outlays. For instance, does an advertising campaign merely incur charges for one period or does it create an asset, such as a brand?

The company’s operating profit

From EBITDA, associated with the operating cycle, we subtract non-cash costs, including depreciation, amortization, impairment losses, or write-downs on fixed assets. This deduction yields operating income, operating profit, or EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes), reflecting the wealth increase generated by the company’s industrial and commercial activities over a specific period.

Operating profit or EBIT represents the earnings derived from both investment and operating cycles within the designated time frame. The term “operating” stands in contrast to “financial,” delineating the separation between the tangible world and financial realms. Operating income is the result of the company’s industrial and commercial activities before factoring in financing operations, and it may also be referred to as operating income, trading profit, or operating result.

The financial cycle

Debt Capital: Repayments on borrowings are not considered costs but rather reimbursements, as implied by their name. Obtaining a loan does not augment wealth, and similarly, repaying a loan does not constitute an expense. The income statement exclusively displays costs associated with borrowings, omitting loan repayments, which are subtracted from the debt documented on the balance sheet. This emphasis is necessary due to common errors encountered in this domain. Conversely, interest payments on borrowings diminish the company’s wealth and hence qualify as expenses, appearing on the income statement. The variance between financial income and financial expense is labeled net financial expense/income. The disparity between operating profit and net financial expense is denoted profit before tax and non-recurring items.

Shareholders’ Equity: From a cash flow perspective, shareholders’ equity stems from share issuance minus outflows in dividends or share buy-backs. These cash injections confer ownership privileges over the company. The income statement gauges the company’s wealth generation, culminating naturally in net earnings (or net profit). Whether these earnings are disbursed as dividends is a straightforward decision regarding the shareholder’s cash position. A broader view reveals that net earnings and financial interest both operate on the principle of distributing the company’s generated wealth. Similarly, income tax represents earnings remitted to the state despite its absence in funding the company.

Recurrent and non-recurrent items

We have now examined all the business operations that can be assigned to the operating, investing, and financing cycles of a company. However, categorizing the financial impacts of certain extraordinary events poses challenges. Events like losses from earthquakes, natural disasters, or government asset expropriation are unpredictable and beyond a company’s control. Hence, a separate category for such extraordinary items is warranted.

On a future article, we’ll go into the complexities of distinguishing between recurring and non-recurring items, compounded by the lack of clarity from accounting regulatory bodies. Among various exceptional events, we’ll briefly discuss asset disposals. While investing is crucial for businesses, disinvestment is also significant. It yields exceptional inflows labeled “asset disposal” on the cash flow statement and capital gains or losses, often categorized as exceptional items.

By definition, it is easier to analyze and forecast profit before tax and non-recurrent items than net income or net profit, which is calculated after the impact of non-recurrent items and tax.

Net income

Net income represents the measure of wealth creation or destruction over the fiscal year. It’s a wealth metric rather than a cash indicator, encompassing non-cash elements like depreciation that contribute to wealth erosion. Often, it doesn’t reflect value increases, which are typically recognized only upon asset sales.

2. DIFFERENT INCOME STATEMENTS FORMATS

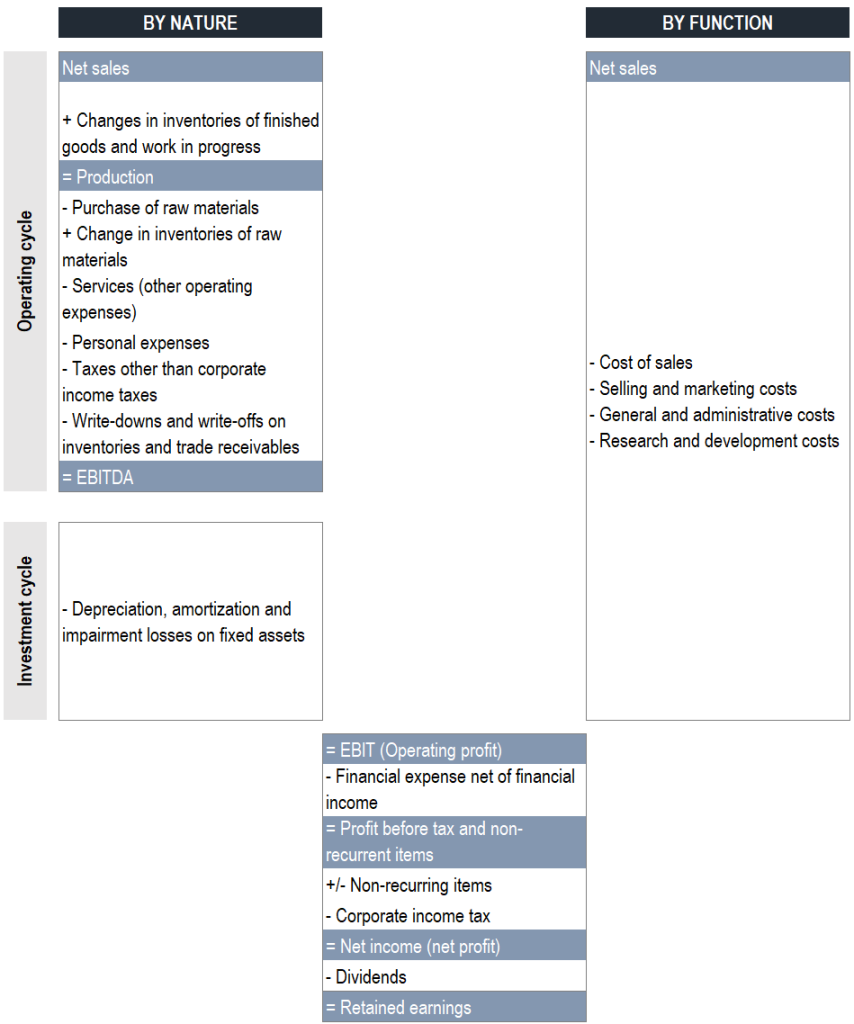

Two primary formats of income statement are commonly employed, differing in their portrayal of revenues and expenses associated with operational and investment activities. They may be categorized as follows:

- Functional presentation: Organizes revenues and costs based on their uses in operational and investment cycles. This format typically includes the cost of goods sold, selling and marketing expenses, research and development outlays, and general and administrative costs

- Nature presentation: Arranges revenues and expenses by type, illustrating changes in inventories of finished goods and work in progress, purchases and alterations in inventories of goods for resale and raw materials, other external expenditures, personnel costs, taxes and duties, depreciation and amortization

The nature presentation format predominates significantly in countries like Italy, India, Spain, and Belgium. Conversely, the functional presentation is predominantly used in the US, with minimal use of other formats.

While historically, France, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK favored either the nature or function format, the current landscape is more varied. Additionally, a new format is gaining traction, primarily a functional approach, although with depreciation and amortization isolated on a separate line, distinct from other costs.

These distinct income statement formats can be summarized by the following diagram:

The by-function income statement format

This presentation is based on a management accounting approach, in which costs are allocated to the main corporate functions.

Consequently, personal expenses are distributed among these four categories (or three in cases where selling, general, and administrative costs are combined) based on the department where an employee works, whether it’s production, sales, research, or administration. Similarly, depreciation expenses for tangible fixed assets are allocated to different categories depending on their usage: production machinery, vehicles for sales teams, laboratory equipment for research and development, or computers for general administrative tasks, such as those used in the accounting department.

This approach adheres to a straightforward principle, illustrating that operating profit results from the variance between sales and the cost of sales, regardless of their specific function (e.g., production, sales, research and development, administration). However, it doesn’t explicitly distinguish between operating and investment activities because depreciation and amortization are not directly presented on the income statement. Instead, they are distributed across the four main corporate functions, necessitating analysts to seek this information in the cash flow statement or in the accompanying notes to the financial statements.

The by-nature income statement format

This is the conventional structure of income statements in many continental European nations, although some conglomerates are shifting towards the by-function layout in their consolidated financial statements. The by-nature format is straightforward to implement, even for small enterprises, as it doesn’t necessitate expense allocation. It offers a more intricate breakdown of costs. As in the preceding method, operating profit remains the difference between sales and the cost of sales.

In this format, costs are recognized when incurred, not when the related items are utilized. Displaying all purchases and invoices sent to customers during the same period wouldn’t provide a fair comparison.

During a fiscal year, a company may move some purchases to inventory. This doesn’t deplete wealth but rather forms an asset, although potentially temporary, with tangible value at a specific time. Additionally, some products manufactured by the company might not be sold within the year, yet the corresponding costs still appear on the income statement.

To ensure a fair comparison, it’s necessary to:

- Remove changes in inventory of raw materials and goods for resale from purchases to determine used raw materials and goods for resale, rather than simply purchased ones

- Add changes in inventory of finished products and work in progress back to sales

Consequently, the income statement displays production rather than just sales. The by-nature format presents the production expenditure for the period, adhering to the accruals convention. However, it has the logical drawback of implying that changes in inventory are revenue or expenses in themselves, which they are not. They are merely adjustments to purchases to derive relevant costs.

Now that we’ve covered the concept of income, in the next article, we’ll delve into Economic assets and financial resources through the study of the balance sheet, which remains a fundamental concept for understanding the financial position of the company at a specific moment.