The purpose of consolidated accounts is to present the financial situation of a group of companies as if

they formed a single entity. This article addresses the fundamental aspects of consolidation that should

be understood by anyone interested in corporate finance. Analyzing the accounting documents of each

individual company within a group does not provide an accurate or useful insight into the economic

health of the entire group. A company’s accounts reflect its control over other companies only through

the book value of its shareholdings and the size of the dividends it receives.

1. CONSOLIDATION METHOD

Any firm that exclusively controls or significantly influences other companies should prepare

consolidated accounts and a management report for the group. Consolidated accounts must be certified

by statutory auditors and, along with the group’s management report, made available to shareholders,

debtholders, and all other stakeholders. Listed European companies have been required to use IFRS

accounting principles for their consolidated financial statements since 2005, and groups from many

other countries have also been required or allowed to adopt these standards since then. The companies

to be included in the preparation of consolidated accounts form what is known as the scope of

consolidation. The scope of consolidation includes:

- The parent company

- Companies in which the parent company has significant influence, assumed when the parent

holds at least 20% of the voting rights

However, a subsidiary should not be consolidated when its parent loses the power to govern its financial

and operating policies, such as when the subsidiary comes under the control of a government, court, or

administration. In such cases, subsidiaries should be accounted for at fair market value. The basic

principle behind consolidation is to replace the historical cost of the parent’s investment in the subsidiary

with its assets, liabilities, and equity.

For example, consider a company with a subsidiary recorded on its balance sheet at an amount of 20.

Consolidation entails replacing this historical cost of 20 with all or some of the assets, liabilities, and

equity of the subsidiary. There are two methods of consolidation used, depending on the strength of the

parent company’s control or influence over its subsidiary.

We will now examine each of these two methods in terms of its impact on sales, net profit and

shareholders’ equity.

Full consolidation

A subsidiary’s accounts are fully consolidated if the parent company controls it. Control means the

parent can direct the subsidiary’s financial and operational policies to gain benefits. Control is presumed

when the parent company:

- Holds more than 50% of the voting rights, directly or indirectly

- Holds less than 50% but can control more than 50% through agreements with other investors

- Can govern the subsidiary’s policies under a statute or agreement;

- Can cast the majority of votes at board meetings or

- Can appoint or remove the majority of the board members

IFRS standards focus on control, while US GAAP emphasizes majority voting rights. The definition can

also include companies with a minority stake or no shares. Full consolidation involves adding all the

subsidiary’s assets, liabilities, and equity to the parent company’s balance sheet and including all the

subsidiary’s revenues and expenses in the parent company’s income statement. This replaces the

investments held by the parent company with the subsidiary’s financial data.

If the parent doesn’t fully control the subsidiary, the interests of minority shareholders in the subsidiary’s

equity and net income must also be shown in the consolidated balance sheet and income statement.

This ensures the financial statements accurately reflect the whole group’s financial position and

performance.

Assuming there is no difference between the book value of the parent’s investment in the subsidiary and

the share of the book value of the subsidiary’s equity, full consolidation works as follows:

- On the balance sheet:

- The subsidiary’s assets and liabilities are added item by item to the parent company’s balance sheet

- The historical cost amount of the shares in the consolidated subsidiary held by the parent is removed from the parent company’s balance sheet and deducted from the parent company’s reserves

- The subsidiary’s equity (including net income) is added to the parent company’s equity and then allocated between the interests of the parent company (added to its reserves) and those of minority investors in the subsidiary (if the parent company does not hold 100% of the capital), which is shown as a special minority interests’ line below the parent company’s shareholders’ equity

- On the income statement, all the subsidiary’s revenues and expenses are added item by item to the parent company’s income statement. The parent company’s net income is then divided into:

- The portion attributable to the parent company, which is added to the parent company’s net income on both the income statement and the balance sheet

- The portion attributable to third-party investors, which is shown on a separate line of the income statement under “minority interests”

Minority interests are the portion of equity and net income of fully consolidated subsidiaries belonging to

minority shareholders. For solvency, minority interests count as shareholders’ equity. However, they do

not add value to the group since they belong to third parties, not the parent company’s shareholders.

Financial analysis assumes the parent owns 100% of the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities until the

penultimate line of the income statement, reflecting an economic, not legal, perspective.

For example, if the parent company owns 75% of the subsidiary.

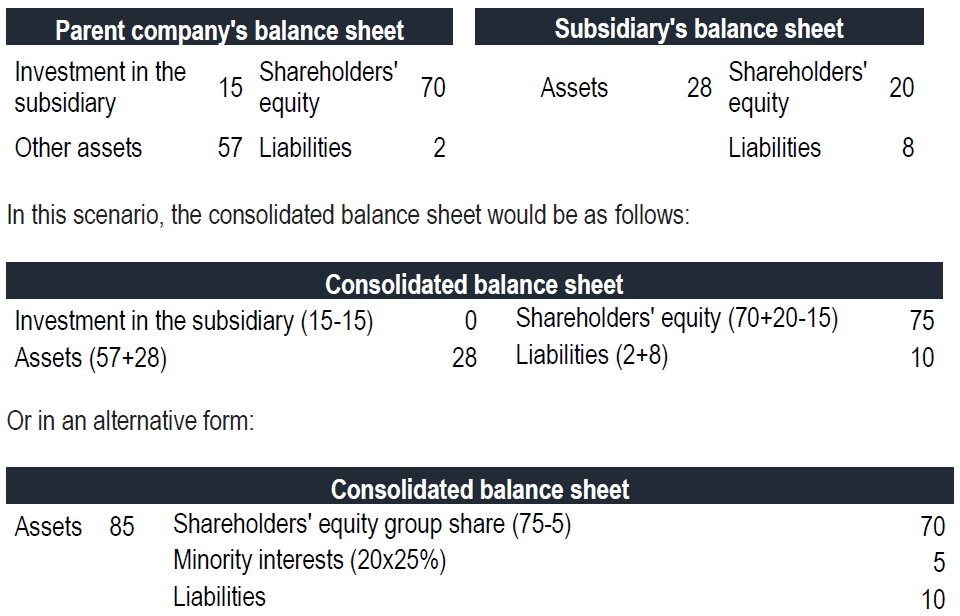

The original balance sheet are as follows:

Group assets and liabilities include both the parent company’s and its subsidiary’s assets and liabilities.

Group equity equals the parent company’s equity plus the subsidiary’s retained earnings since

consolidation began. Minority interests represent the share of the subsidiary’s equity and net income

attributable to minority shareholders.

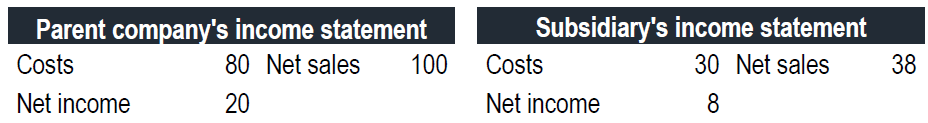

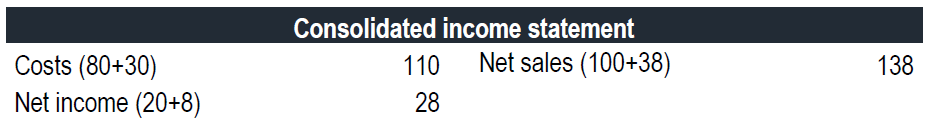

The original income statements are as follows:

In this scenario, the consolidated income statement would be as follows:

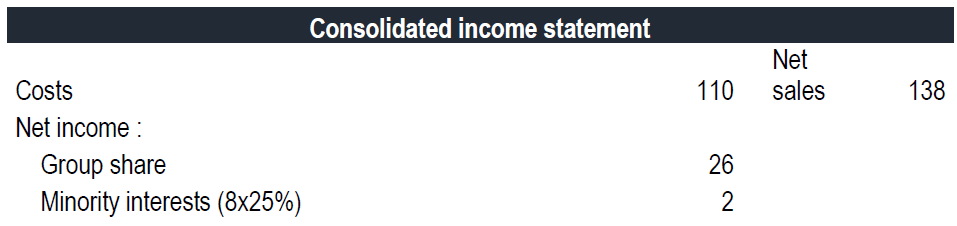

Or, in a more detailed form:

Equity method of accounting

When the parent company has a significant say in its associate’s operations and finances, it uses the

equity method, typically when it holds at least 20% of the voting rights. This method replaces the parent

company’s shareholding’s historical cost with its portion of the associate’s equity (excluding associate

income), focusing more on financial evaluation than consolidation.

Technically, equity accounting involves:

- Replacing the historical cost of shares with the parent company’s share of the associate’s

equity; - Adjusting the parent company’s reserves accordingly;

- Adding the parent company’s share of the associate’s net income to both the parent company’s

net income and the income statement.

Investments in associates reflect the parent company’s equity attributed to associates. While the equity

method increases the carrying amount of the shareholding on the consolidated balance sheet yearly, it

doesn’t give a clear picture of the group’s risk exposure to its associate, limiting the group’s risk to the

value of its shareholding.

2. CONSOLIDATED-RELATED ISSUES

Scope of consolidation

Determining the consolidation scope involves evaluating how much control the parent company has

over its subsidiaries, joint ventures, or associates. Control is gauged by the percentage of voting rights

held. To assess control, we examine the voting rights percentage held by all group companies in the

subsidiary. Control is typically assumed when this percentage reaches 50% or more. It’s essential to

distinguish control from ownership, as ownership represents the financial claims of the parent company

on its entities, whereas control is more about authority. Ownership is calculated by summing up the

direct and indirect percentage stakes held by the parent company in an entity. Unlike control, ownership

considers all subsidiaries, not just the controlled ones.

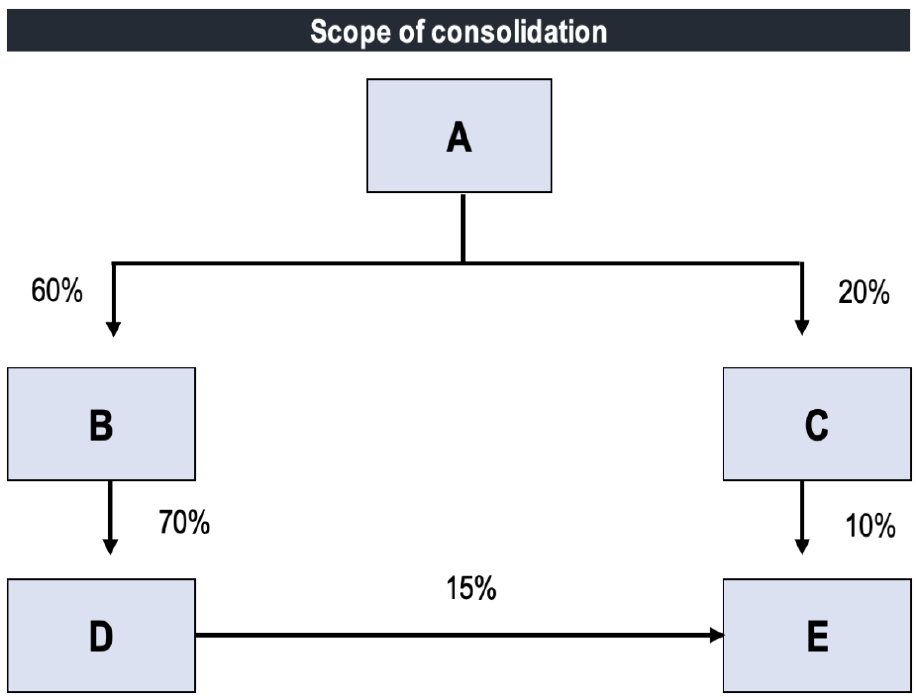

A owns 60% of B, and B controls 70% of D, so A effectively controls 70% of D. Thus, D and B are

considered controlled and fully consolidated by A. However, A’s ownership of D is only 42% (i.e., 60% ×

70%). Therefore, A’s ownership level over D is 42%, meaning only 42% of D’s net income is attributed

to A. Since C holds just 10% of E, it doesn’t consolidate E. Similarly, D, owning only 15% of E, doesn’t

consolidate it either. However, as A controls 20% of C, it will account for C using the equity method and

include 20% of C’s net income in its income statement. A’s ownership level over E is calculated as 20%

× 10% + 60% × 70% × 15% = 8.3%. A’s control percentage over E is 15%.

The use of the ownership level varies depending on the consolidation method:

- With full consolidation, the ownership level determines the allocation of the subsidiary’s

reserves and net income between the parent company and minority interests. - With the equity method, the ownership level helps determine the portion of the subsidiary’s

shareholders’ equity and net income attributable to the parent company.

The goodwill

Goodwill is a concept in business accounting that arises during acquisitions. It represents the intangible

value a buyer sees in a target company beyond its tangible assets and liabilities. When one company

purchases another, the purchase price may exceed the sum of the target company’s identifiable assets

and liabilities. This excess amount is recorded as goodwill. It encompasses various intangible assets,

such as brand reputation, customer loyalty, employee relations, patents, and proprietary technology.

These assets contribute to the overall value of the acquired company but are not separately identifiable

or quantifiable. In accounting, goodwill is calculated by subtracting the fair market value of the

identifiable assets and liabilities from the purchase price. If the purchase price exceeds the fair value of

the assets and liabilities, the excess amount is recorded as goodwill on the buyer’s balance sheet.

For example, if Company A acquires Company B for $1 million and the fair value of B’s identifiable

assets and liabilities is $800 000, then the goodwill recorded by Company A would be $200 000.

3. CONSOLIDATED-RELATED ISSUES

Aligning accounting data

Consolidation involves combining accounts with some adjustments, so it’s crucial to ensure consistency

in the accounting data used. Typically, individual company accounts use valuation methods influenced

by specific accounting or tax regulations, especially for subsidiaries abroad. This affects provisions,

depreciation, fixed assets, inventories, deferred charges, and shareholders’ equity.

These disparities must be resolved during consolidation. Since consolidated accounts are often not

used for tax calculation, groups can disregard tax regulations. Before consolidation, the consolidating

company adjusts the accounts of subsidiaries. It applies the same valuation principles and adjusts for

differences justified by tax regulations, such as tax-regulated provisions and accelerated depreciation.

Removing intra-group transactions

Consolidation involves more than just combining accounts. Before consolidation begins, intra-group

transactions and their impact on net income must be eliminated from both the parent company’s and its

subsidiaries’ accounts.

For example, if the parent company sells products to subsidiaries at a markup, any unrealized gain in

the group’s accounts needs to be removed if the products are not sold to external parties.

Intra-group transactions to be eliminated fall into two categories:

- Significant transactions: These affect consolidated net income and must be reversed to avoid duplicating profits or showing the same profit twice. They include:

- Intra-group profits in inventories

- Capital gains from investment transfers

- Dividends received from subsidiaries

- Impairment losses on intra-group loans or investments

- Taxes on intra-group profits

- Non-fundamental transactions: These have no impact on consolidated net income or assets/liabilities of the group. They are eliminated through netting to show the true level of the group’s debt. Examples include:

- Loans between parent and subsidiary

- Interest payments between the parent company and subsidiaries