Before diving into a company’s financials, readers should evaluate its strategic and economic landscape. This involves assessing its industry, market position, production model, distribution network, and ownership structure. Reviewing the auditors’ report and accounting principles is crucial as well. Financial analysis aims to depict a company’s economic reality, not just numbers. Without considering this reality, analysis may lack insight and fail to identify underlying issues until they appear in the financials, too late for investors to react. Once this groundwork is done, readers can proceed with standard analysis methods and advanced tools like credit scoring.

1. BASICS

Financial analysis serves various stakeholders like shareholders, lenders, and rating agencies. For shareholders, it evaluates a company’s value creation potential, often resulting in buy or sell recommendations. Lenders use it to gauge solvency and liquidity, determining the company’s ability to meet obligations and repay debts promptly. While the objectives differ, the analysis techniques remain the same because a value-creating company tends to be solvent, whereas a value-destroying one may face solvency issues eventually. Both shareholders and lenders closely examine a company’s cash flow statement, crucial for debt repayment and generating shareholder value.

Financial analysis relies heavily on economic and accounting data, aiming to provide insights into a company’s reality through figures. Although it involves dealing with complex data, it can often be simplified with sector knowledge and common sense. Analysts adjust accounting figures as needed to better reflect economic reality. Internally or externally, financial analysis offers a holistic view of a company’s present and future status, emphasizing understanding its strategy and performance.

Effectiveness in financial analysis is not about using sophisticated techniques but uncovering inaccuracies or underlying problems in accounting data. Analysts piece together a company’s economic model, comparing it with competitors to identify chronic weaknesses versus temporary issues. Recognizing that financial statements represent a balance between various factors is crucial for accurate analysis, avoiding hasty judgments based on isolated incidents in financial data.

2. ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF COMPANIES

The company’s market

Understanding a company’s market is essential. Markets are defined by consistent behaviors and needs met through similar distribution channels. For example, the pay-TV market includes operators like BSkyB and Canal+, with competition from cinemas and live events. Accurate market segmentation by geography and sociology helps gain a competitive edge. For instance, a 30% share in the German running shoe market seems significant but is limited globally.

Analysts assess growth opportunities and risks after defining a market. Organic growth is challenging in developed countries, so mature economies focus on value growth through innovation. Growth drivers include technology, consumer behavior changes, and environmental concerns. Expanding sectors aren’t always lucrative, as seen with video games, while mature markets like tobacco yield high returns. Market risk varies between original and replacement products. Original equipment sales appeal to new

consumers, while replacements depend on economic conditions. Analysts must understand product acquisition patterns to gauge economic sensitivity. Stable sectors like food can have overlooked risks.

A company’s market share indicates its business volume or value. High market share offers advantages like customer loyalty and strong bargaining positions. However, market share isn’t always relevant, as seen in construction and public works. Acquiring market share through price cuts without retaining it is futile. In expanding markets, it’s better to have smaller rivals. In mature markets, niche-specialized companies benefit from large rivals avoiding them. Stable markets with many small rivals often lead to price wars. Understanding competitors’ motivations is crucial, as some prioritize power over profitability.

Competition is either price-driven or product-driven. Price-driven focuses on cost control and economies of scale, making market share vital. Product-driven emphasizes service, quality, and brand image. Real-world competition often blends both approaches.

The production

A value chain includes all companies involved in manufacturing, from raw materials to end products. It may involve raw material processing, R&D, trading, and distribution. In a service-oriented society, value chains often involve services rather than physical processing. Analyzing a value chain helps understand market participants’ roles, strengths, and weaknesses. During crises, some participants suffer more than others, with structural weaknesses often determining vulnerability. Analysts aim to identify risky investments within the chain. In a service-based economy, industrial production models are often overlooked but are worth examining. Analysts assess factors like production responsibility, location, and workforce composition to gauge income statement flexibility.

There are four types of industrial organizations:

- Project-based: Economically minor

- Workshop: Suitable for craftsmen or luxury goods but impractical for scalability

- Mass production: Low unit cost but high working capital due to inventory

- Process-specific: Revolutionized production, with low working capital but vulnerability to supply disruptions

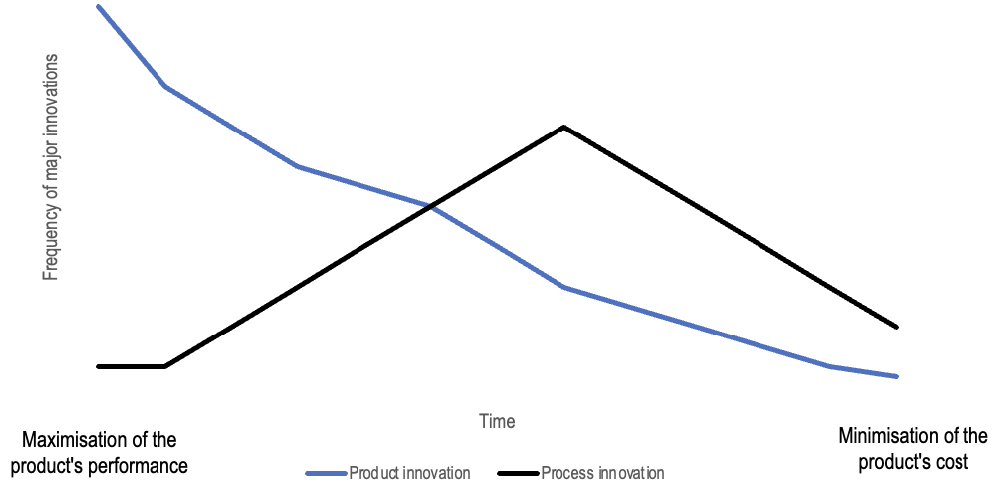

Analyzing these processes helps evaluate business strategy alignment with production models. It’s essential to consider each model’s advantages and disadvantages and how they fit the company’s strategy. A company should avoid early investment in production. Initially, a new product must prove its suitability to consumers before evolving with minor features and increased sales. Once established, focus shifts to cost reduction. Innovation efforts move from product to production model refinement.

Investing prematurely in production poses risks and may divert funds from crucial product anchoring and market initiatives. Outsourcing production mitigates such risks until stability is achieved. Once production stabilizes, internalizing operations can optimize productivity and lower costs. In contemporary business, outsourcing is common, with companies focusing on design and management. Value has shifted from production to research, innovation, and marketing. Coordination with external manufacturers, exemplified by companies like Foxconn and Flextronics, enables cost-effective production through economies of scale.

The distribution systems

A distribution system fulfills three key roles:

- Logistics: Displaying, delivering, and storing products

- Advice and Services: Providing product details, after-sales service, and information exchange between producer and consumer

- Financing: Purchasing products and assuming sales risk

If any of these roles are lacking, the producer faces difficulties in expanding. For example, in the retail furniture sector, limited financing and logistics weaken producers who cannot build strong brands, unlike private labels like IKEA. Producers and distributors share the goal of selling products, though they may argue over price shares. A producer’s efficiency depends on an effective distribution network. The choice of distribution system is crucial. Directly managing distribution allows for faster response to customer preferences and market changes but requires significant investment and skills. This approach is beneficial when product image, after-sales service, and quality are crucial, as seen with Burberry’s strategy to reclaim its franchises. Conversely, minimal investment in distribution keeps the company distant from customers, risking delayed responses to market fluctuations. In price-sensitive markets, producers should invest in production to lower costs, with the Internet offering a cost-effective distribution alternative.

Company and people

It is often said that a company’s human resources are crucial, particularly in smaller firms where the personal qualities of managers can be pivotal. However, it’s essential for management to establish strategic positions that add value beyond just the founder or manager.

Shareholders:

The most important people in a company are its shareholders, who appoint executives and set strategy. Shareholders can be classified as inside (also managers) or outside. Inside shareholders have significant personal stakes and are closely tied to the company’s fate, but may struggle to make tough decisions due to emotional ties. Outside shareholders, driven by financial interests, can provide useful guidance but might act passively during crises. Analysts should be wary of conflicts among shareholders that could hinder the company’s operations.

Managers:

Understanding managers’ objectives and their relationship with shareholders is key. Stock-option-based incentives have aligned managers’ interests with those of shareholders. However, caution is needed when these incentives extend to most employees, as it can lead to instability during downturns. Top talent may leave quickly to cash in their stock options, while those remaining may not recognize problems until it’s too late, worsening the situation.

Corporate Culture:

Corporate culture is crucial, especially during acquisitions or diversification. A rigid, centralized company may struggle to integrate with more dynamic targets. For example, Daimler’s acquisition of Chrysler failed due to cultural clashes between Daimler’s structured approach and Chrysler’s innovative environment.

3. THE COMPANY’S ACCOUNTING POLICY

Analyzing the auditors’ report and accounting principles is crucial before conducting a financial analysis of a company’s accounts. If the accounting principles align with standard practices, the accounts likely reflect the company’s economic reality accurately. However, if there are anomalies or deviations from the norm, the accounts are distorted. In such cases, lenders should avoid extending credit, and shareholders should avoid buying or promptly sell any held shares. Deviating from standard accounting principles typically indicates an attempt to disguise an unfavorable reality.

4. FINANCIAL ANALYSIS PLAN

Novices often struggle with their first financial analysis, producing descriptive comments without internal consistency or causal links. Financial analysis is a logical investigation requiring interconnected parts. Analysts act as detectives, searching for clues and establishing a logical sequence while identifying potential problems. Wealth creation requires investment, which must be financed and yield sufficient

returns. A company remains viable if it attracts customers who buy its goods or services at prices that ensure operating profit. Therefore, examining the company’s earnings structure is essential. To start operations, a company must invest in fixed assets and working capital, forming its capital employed, financed through equity or loans.

Once margins, capital employed, and financing are examined, the company’s efficiency can be calculated via return on capital employed (ROCE) or return on equity (ROE). This determines if the company can honor creditor commitments and create shareholder value.

Analysts should study:

- Wealth creation: trends in sales, prices, and volumes; business cycles; EBITDA and EBIT margins; scissors effect, and operating leverage

- Capital employed policy: capital expenditure and working capital

- Financing policy: debt, equity, or internally generated cash flow, using the cash flow statement and balance sheet

- Profitability: ROCE, ROE, leverage effect, and comparing profitability with required return rates to assess value creation and solvency.

5. FINANCIAL ANALYSIS TECHNIQUES

Trend Analysis

Financial analysis examines trends over multiple years (usually at least three) to understand past performance, assess the present, and forecast the future. Analysts must detect potential deterioration by examining trends, not just key profit indicators. However, trend analysis is valid only if the data are comparable year-to-year and timely, which can be challenging due to changes in business activities, models, consolidation, or accounting rules. Additionally, published accounting information is often delayed, giving internal analysts an advantage with quicker access to data.

Comparative Analysis

Comparative analysis evaluates a company’s key profit indicators against those of similar companies in the same sector, helping to determine relative viability. This method is used by financial analysts, companies setting customer payment periods, banks, and others assessing financial structures. Benchmarking involves using data from organizations like central banks or rating agencies, which compile and publish financial characteristics of companies. Drawbacks include the vague concept of sectors and the risk of mass delusion leading to overvalued stocks.

Normative Analysis

Normative analysis extends comparative analysis by comparing company ratios to industry-specific norms or general financial rules of thumb. For instance, in the hotel industry, the bed-per-night cost should be at least 1/1000 of the room’s construction cost. General rules include financing fixed assets with stable funds and keeping net debt no greater than three times EBITDA. However, these norms, derived from statistical studies, can lack conceptual robustness and are difficult to interpret, except in capital structure contexts. Ultimately, profitability is the key determinant of a company’s actions and success.

6. RATINGS & SCORING TECHNIQUES

Credit ratings assess a borrower’s solvency, provided by agencies like Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch, banks, and credit insurers. Ratings reflect the borrower’s ability to honor payments and the borrowing’s specific characteristics. The rating process includes evaluating strategic risks and financial health, such as operating margins, return on capital, and capital structure. These ratings are crucial for understanding financial risk.

Credit scoring, an automated analysis technique, predicts potential company difficulties by calculating ratios from financial statements, which are then compared to those of troubled companies. The Z-score, derived from these ratios, indicates a company’s probability of encountering problems within the next two to three years. This technique enhances traditional ratio analysis by weighting ratios based on their predictive power.

However, scoring has drawbacks. It requires a large, accurate, and consistent sample over a sufficient period to identify trends. Scoring equations must be updated regularly to remain relevant. Additionally, these equations are primarily designed to predict small and medium-sized enterprises’ failure risk and are less effective for other purposes or large groups. Scoring techniques can also create a self-fulfilling prophecy, where identified risks lead to behaviors that hasten a company’s decline.